Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods|

Read More

Date: 2024-08-29

Date: 11-2-2022

Date: 2023-03-28

|

Consequences of modifying Gunlogsons 2001 model

In this section I discuss a consequence of my interpretation and application of Gunlogson’s model. In this analysis I have made two modifications to Gunlogson’s proposal. First, I have updated her model and incorporated previous research on vagueness by making the model sensitive to degrees. Second, by appealing toWalker’s Collaborative Principle, I make a non-trivial (and somewhat controversial) leap: I allow for the possibility that a speaker’s utterance may have a substantive effect on the representation of the addressee’s commitment set.1 Having made these modifications, I point out how a combination of Gunlogson’s analysis of rising and falling intonation and the proposed semantics of clear make a prediction about a strategy a speaker might use to signal commitment on the part of both the speaker and the addressee with the utterance of a single sentence.

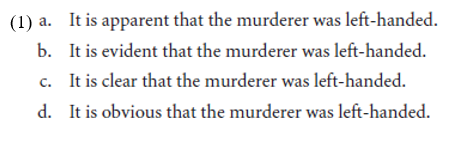

Regarding the incorporation of degrees into the analysis, this modification provides a means of representing degrees of public commitment to a proposition. This is a welcome consequence, since a comparison across the class of discourse adjectives reveals that an individual’s degree of public commitment toward a proposition can be more or less strong. Consider the sentences in (1), as possibly uttered by Briscoe upon his arrival and after a brief survey of the scene of a crime.

If Briscoe utters (1a) and later finds out that the murderer was in fact righthanded, one might reasonably expect him to be mildly surprised. However, if he had instead uttered (1d), one could reasonably find it odd if he showed only mild surprise if he later learned that the murderer was not left-handed. This suggests that obvious has a higher minimum standard for “probability in light of evidence” than does apparent. Following Taranto (2006), I posit that clear and obvious have higher minimum standards for probability in light of evidence than do apparent and evident. The choice of one discourse adjective over another may indicate a greater or lesser degree of commitment to the truth or likelihood of an embedded proposition.

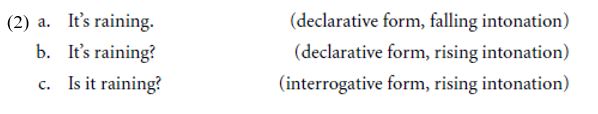

In order to discuss the effect of modifying Gunlogson’s proposed model, it is necessary to introduce the data that led her to isolate the individual commitment sets of the speaker and addressee in a discourse. Gunlogson’s concern was the interaction of intonation and sentence form, and the contributions that both rising and falling intonation make as they interact with declarative and interrogative sentence forms. In the examples in this section, a question mark (?) indicates rising intonation, while a period (.) indicates falling intonation.

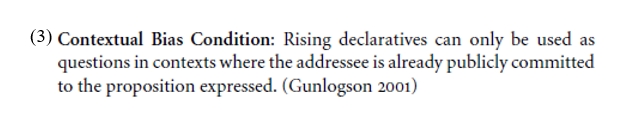

Gunlogson’s work addressed the ability of a declarative sentence with rising intonation to be used as a question, as in (2b). Her observation was that with falling intonation, an utterance of It’s raining conventionally implicates a speaker’s commitment to the content of the proposition expressed by that sentence, while an utterance of It’s raining? with rising intonation conventionally implicates commitment on the part of the addressee. She further notes that a condition on the appropriate use of (2b) is that the context must already be biased toward the proposition expressed by It’s raining by virtue of the addressee’s prior public commitment to them. By positing a model that isolates the individual commitments of the discourse participants, she is able to capture this restriction in the form of the Contextual Bias Condition, stated descriptively in (3).

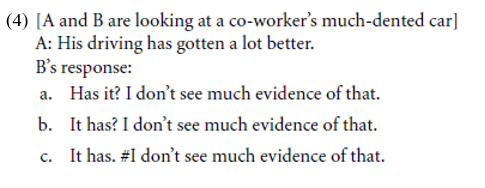

Without appealing to vagueness or degrees of commitment, Gunlogson shows that rising declaratives pattern like interrogatives in allowing a reading in which the speaker is understood to be skeptical of the proposition expressed. Falling declaratives cannot cooccur with overt expressions of skepticism. An example she provides to illustrate this fact is given in (4).

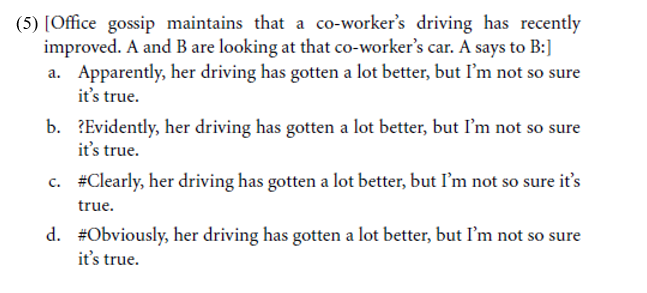

In terms that incorporate vagueness, this can be restated as follows: rising intonation signals a degree of commitment to the truth of a proposition that is less than the minimum standard for absolute commitment, while falling intonation signals a degree of commitment that is at least as great as that standard. While the relationship between the discourse adjectives and discourse adverbs is a question for future research, Gunlogson’s diagnostic might be translated into a diagnostic for degrees of commitment involved with derivationally related discourse adverbs, as in (5).

Though not all speakers agree that the (a) and (b) sentences are good, for those who find the (a) and (b) sentences better than the (c) and (d) sentences, the difference in acceptability of these utterances is explained through consideration of degrees of probability. Specifically, the adverbs derived from apparent and evident impose relatively loose standards with respect to the minimum degree of probability they tolerate. This allows the speaker to remain skeptical of the truth of the proposition expressed by Her driving has gotten a lot better. Because of this, assertions with apparently or evidently are more compatible with overt expressions of doubt, as in (5a) and (5b).

In contrast, the sentences with clearly and obviously impose a higher minimum standard of probability, and do not allow such overt expressions of doubt. Inconsistency results when sentences with adverbs derived from clear and obvious are uttered with a skeptical follow-up. Thus clear and obvious pattern like falling declaratives in strongly committing the speaker to the proposition expressed.

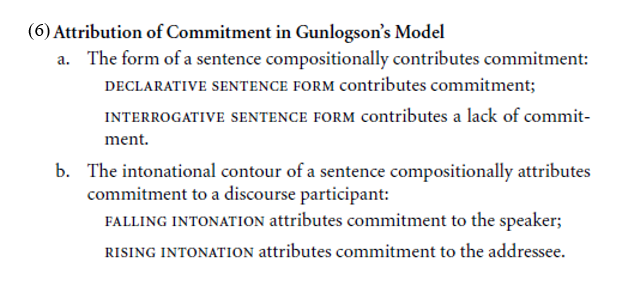

These points about degrees of commitment lead to a final observation regarding the notion of commitment. This has to do with the attribution of commitment to individual participants in a discourse. As summarized in (6), Gunlogson shows that a speaker can use falling intonation to signal her own commitment to the propositional content of an utterance, and a speaker can use rising intonation to signal commitment on the part of the addressee.

A natural question to ask is: How does a speaker signal commitment on the part of both herself and the addressee – that is, all of the discourse participants – to the propositional content of an utterance? There appears to be no intonational contour that serves this function in English. But the analysis presented in this chapter shows that discourse adjectives fill this role in the grammar. The use of a discourse adjective in a declarative sentence with falling intonation is a strategy a speaker can adopt to commit both speaker and addressee to the content of a proposition by uttering a single sentence, such as the core example of this chapter, It is clear that Briscoe is a detective.

Further, this analysis of discourse adjectives, combined with Gunlogson’s compositional analysis of rising intonation, makes a prediction about the meaning of an utterance of a declarative sentence with a discourse adjective and rising intonation, as in (7).

(7) It’s clear that Briscoe is a detective?

The prediction is that an utterance of (7) signals a commitment on the part of the addressee to the belief that the interlocutors agree that Briscoe is a detective. This prediction is borne out. The combination of Gunlogson’s Contextual Bias Condition with the semantics provided here for discourse adjectives accurately captures the semantics of (7), as well as the intuition that its utterance can only be felicitously uttered in a situation that is contextually biased toward both discourse participants already being committed to the proposition expressed by It is clear that Briscoe is a detective.

1 The analysis of discourse adjectives presented here is not meant to dispute Gunlogson’s analysis. The claim made here is merely that more than the notion of contextual bias is needed in order to accurately describe the semantics of these adjectives.

|

|

|

|

لشعر لامع وكثيف وصحي.. وصفة تكشف "سرا آسيويا" قديما

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

كيفية الحفاظ على فرامل السيارة لضمان الأمان المثالي

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تجري القرعة الخاصة بأداء مناسك الحج لمنتسبيها

|

|

|