علم الكيمياء

علم الكيمياء

الكيمياء التحليلية

الكيمياء التحليلية

الكيمياء الحياتية

الكيمياء الحياتية

الكيمياء العضوية

الكيمياء العضوية

الكيمياء الفيزيائية

الكيمياء الفيزيائية

الكيمياء اللاعضوية

الكيمياء اللاعضوية

مواضيع اخرى في الكيمياء

مواضيع اخرى في الكيمياء

الكيمياء الصناعية

الكيمياء الصناعية | Molecules with more than one C=C double bond Benzene has three strongly interacting double bonds |

|

|

|

أقرأ أيضاً

التاريخ: 19-9-2019

التاريخ: 7-1-2022

التاريخ: 24-7-2019

التاريخ: 6-10-2020

|

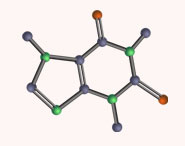

The rest of this chapter concerns molecules with more than one C=C double bond and what happens to the π orbitals when they interact. To start, we shall take a bit of a jump and look at the structure of benzene. Benzene has been the subject of considerable controversy since its discovery in 1825. It was soon worked out that the formula was C6H6, but how were these atoms arranged? Some strange structures were suggested until Kekulé proposed the correct structure in 1865. Shown below are the molecular orbitals for Kekulé’s structure. As in simple alkenes, each of the carbon atoms is sp2 hybridized, leaving the remaining p orbital free.

The σ framework of the benzene ring is like the framework of an alkene, and for simplicity we have just represented the σ bonds as green lines. The difficulty comes with the p orbitals— which pairs do we combine to form the π bonds? There seem to be two possibilities.

With benzene itself, these two forms are identical but, if we had a 1,2- or a 1,3-disubstituted benzene compound, these two forms would be different. A synthesis was designed for the two compounds in the box on the right but it was found that both compounds were identical. This posed a problem to Kekulé—his structure didn’t seem to work after all. His solution—which we now know to be incorrect—was that benzene rapidly equilibrates, or ‘resonates’, between the two forms to give an averaged structure in between the two. The molecular orbital answer to this problem is that all six p orbitals can combine to form (six) new molecular orbitals, and the electrons in these orbitals form a ring of electron density above and below the plane of the molecule. Benzene does not resonate between the two Kekulé structures—the electrons are in molecular orbitals spread equally over all the carbon atoms. However, the term ‘resonance’ is still sometimes used (but not in this book) to describe the averaging effect of this mixing of molecular orbitals. We shall describe the π electrons in benzene as delocalized, that is, no longer localized in specifi c double bonds between two particular carbon atoms but spread out, or delocalized, over all six atoms in the ring.

The alternative drawing on the left shows the π system as a ring and does not put in the double bonds: you may feel that this is a more accurate representation, but it does present a problem when it comes to writing mechanisms. As you saw in Chapter 5, the curly arrows we use represent two electrons. The circle here represents six electrons, so in order to write reasonable mechanisms we still need to draw benzene as though the double bonds were localized. However, when you do so, you must keep in mind that the electrons are delocalized, and it does not matter which of the two arrangements of double bonds you draw.

If we want to represent delocalization using these ‘localized’ structures, we can do so using curly arrows. Here, for example, are the two ‘localized’ structures corresponding to 2-bromo carboxylic acid. The double bonds are not localized, and the relationship between the two structures can be represented with curly arrows which indicate how one set of bonds map onto the other.

These curly arrows are similar to the ones we introduced in Chapter 5, but there is a crucial difference: here, there is no reaction taking place. In a real reaction, electrons move. Here, they do not: the only things that ‘move’ are the double bonds in the structures. The curly arrows just show the link between alternative representations of exactly the same molecule. You must not think of them as showing ‘movement round the ring’. To emphasize this, differ ence we also use a different type of arrow connecting them—a delocalization arrow made up of a single line with an arrow at each end. Delocalization arrows remind us that our simple fixed-bond structures do not tell the whole truth and that the real structure is a mixture of both. The fact that the π electrons are not localized in alternating double bonds but are spread out over the whole system in a ring is supported by theoretical calculations and confirmed by experi mental observations. Electron diffraction studies show benzene to be a regular planar hexagon with all the carbon–carbon bond lengths identical (139.5 pm). This bond length is in between that of a carbon–carbon single bond (154.1 pm) and a full carbon–carbon double bond (133.7 pm). A further strong piece of evidence for this ring of electrons is revealed by proton NMR and discussed in Chapter 13.

|

|

|

|

حقن الذهب في العين.. تقنية جديدة للحفاظ على البصر ؟!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

علي بابا تطلق نماذج "Qwen" الجديدة في أحدث اختراق صيني لمجال الذكاء الاصطناعي مفتوح المصدر

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تكرم أكثر من 650 طالبة مرتدية العباءة الزينبية في الجامعة المستنصرية

|

|

|