Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Evaluative adverbs and dialogue - Evaluatives as ancillary commitments

المؤلف:

OLIVIER BONAMI AND DANIELE GODARD

المصدر:

Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse

الجزء والصفحة:

P285-C9

2025-04-29

707

Evaluative adverbs and dialogue - Evaluatives as ancillary commitments

It has been said in the preceding section that the content of the evaluative adverb is not part of the main content of the sentence in which it occurs. On the other hand, we have also suggested that the speaker is somehow committed to the evaluative comment. We now turn to the special pragmatic status of evaluatives, which accounts for this intriguing double behavior.

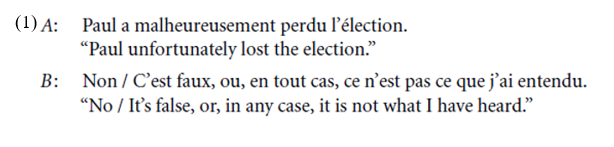

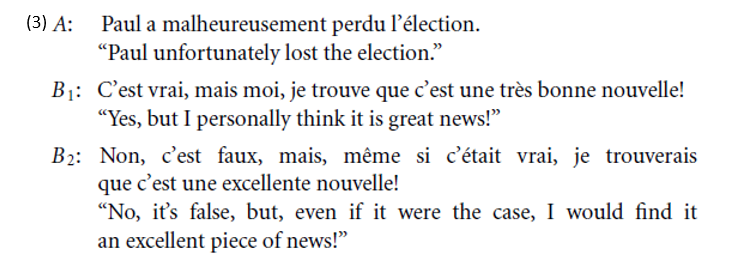

As observed by Jayez and Rossari (2004), evaluatives cannot be challenged by the other discourse participants, at least with ordinary means. Compare the dialogues in (1) and (2). On the other hand, evaluatives can be challenged by a speaker who, at the same time, accepts or rejects the main content (Potts 2005: 51). This requires a special form of answer, such as yes . . . but (3).

This data makes sense if the evaluative adverb denotes the judgment of the speaker independently of the other commitments associated with his discourse. We will say that the evaluative conveys an ancillary commitment of the speaker.

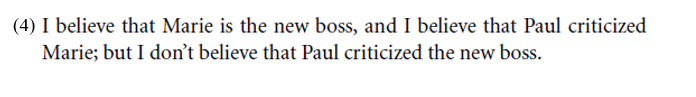

Assuming that evaluative adverbs convey a commitment of the speaker independent of that effected by the main speech act directly accounts for the two basic semantic properties. Since the adverb does not contribute to the main speech act, this speech act gets effected just as if the adverb were absent. Thus if the utterance is an assertion, the speaker is committed to the truth of the proposition conveyed by the sentence without the adverb. As for non-opacity, since we assume that evaluative adverbs take a propositional argument, nothing in their semantics precludes them from triggering opacity. However their special pragmatic status has the required effect. The crucial observation here is that we are dealing with the beliefs of a single agent. If he says (1b), the speaker (assuming sincerity) indicates he believes that (i) Marie is the new boss, (ii) Paul criticized Marie, and (iii) it is unfortunate that Paul criticized Marie. While it is possible for an agent to have contradictory beliefs, it is not so easy to knowingly entertain contradictory beliefs. Thus for a speaker to say (1b) and still deny that Paul unfortunately criticized the new boss would be akin to his asserting (4), which is clearly odd. Thus, just as first person attitude reports are ordinary attitude reports with a special pragmatic status that bars opacity, we assume that evaluative adverbs are proposition modifiers with a special pragmatic status.

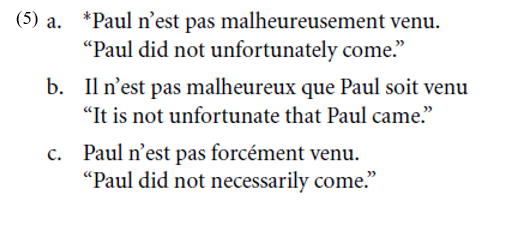

This ancillary commitment hypothesis also explains a well-known observation, which nevertheless has resisted syntactic or logical accounts: in contrast with evaluative adjectives, evaluative adverbs cannot be in the scope of negation.

This cannot be due to type mismatch. First, the negation is also an operator taking a proposition argument, so it suffices that the evaluative does not change the type of the expression it combines with (i.e., that it denotes a function from propositions to propositions) for the negation to find the right argument type. Second, some modal adverbs can occur in the scope of the negation (5c). Note that the scope of (prosodically integrated) postverbal adverbs follows order: an adverb has scope over adverbs on its right. Accordingly, the only possible argument of the evaluative in (5a) is come(p). Thus, according to our analysis, (5a) commits the speaker to the two propositionsi.While these are not contradictory, it is quite odd for a speaker to engage in conditional talk about a proposition which he simultaneously asserts to be false. While this may be done using counterfactuals, it seems that explicit marks of counter factuality is needed for it to be felicitous.

To summarize, evaluatives do not contribute to the main content of the sentence, but they imply a commitment on the part of the speaker. Several analyses have been proposed. The first attempt consisted in associating sentences with evaluatives with two speech acts, one for the main content, and one for the evaluative content (Bartsch 1976; Bellert 1977). Although these analyses delineate the problem, they do not deal with the asymmetric status of the two contents, which do not have the same role in dialogue, as shown above. More recently, Bach (1999) suggested that expressions such as evaluatives constitute ancillary propositions, which are distinct from the main content, but can nevertheless be asserted at the same time as the main content (secondarily). Their occurrence in interrogative sentences noted earlier, where they are not included in the question content and the query speech act, raises a serious problem for this proposal. It seems that we need an ancillary assertion in addition to the query; it is not clear, then, what the difference is with the two speech act proposal. Finally, in two concomitant analyses (Jayez and Rossari 2004; Potts 2005), evaluatives are seen as a case of conventional implicatures in Grice’s (1975) sense: although they are not part of “what is said,” their semantic content is encoded in the grammar. Accordingly, they contribute to an independent dimension of content. While we believe these analyses to be on the right track, they fall short of accounting for the special dialogical status of evaluatives observed in (1–3): we still need to work out what the dialogical status of that independent dimension is. We thus propose an analysis of the pragmatics of evaluatives, integrated in a model of dialogue, a slightly modified version of Ginzburg (2004).

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)