Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Evaluative adverbs and dialogue - Modeling ancillary commitments

المؤلف:

OLIVIER BONAMI AND DANIELE GODARD

المصدر:

Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse

الجزء والصفحة:

P288-C9

2025-04-29

789

Evaluative adverbs and dialogue - Modeling ancillary commitments

We adopt the view that speech acts are best seen as (possibly complex) dialogue moves. Ginzburg’s framework models dialogue moves as updates to a structure he calls the dialogue gameboard. The idea is that each participant keeps a gameboard representing what he assumes to be known to the participants in the current exchange. The gameboard is particular to a participant, although normal conversation usually aims at synchronizing the content of the gameboards. The gameboard contains three parts:

_ The questions under discussion (qud), a partially ordered set of questions.

_ The set of facts that the dialogue participants are publicly committed to.

_ The latest-move, a representation of the preceding dialogue move.

The set of facts is a close analogue to the common ground in the sense of Stalnaker (1978): it contains “a set of facts corresponding to the information taken for granted by the C[onversational] P[articipant]s” (Ginzburg and Cooper 2004: 325). For reasons that will become clear presently, we need to distinguish more directly the participant’s view of the common ground, that is, what he believes is shared knowledge, from what he is publicly committed to, that is, the commitments of that participant in the dialogue (Hamblin 1970). Thus we replace the set of facts by two independent pieces of information:

_ The common ground (cg), a set of propositions.

_ The participant’s commitments (cmt), a distinct set of propositions.

Of course there is a link between the commitments of the dialogue participants and the common ground: once every participant is committed to some proposition, that proposition becomes common ground; but (i) some propositions in the cg correspond to background knowledge that nobody is explicitly committed to, and (ii) a participant may reject a proposition that some other participant is committed to.1

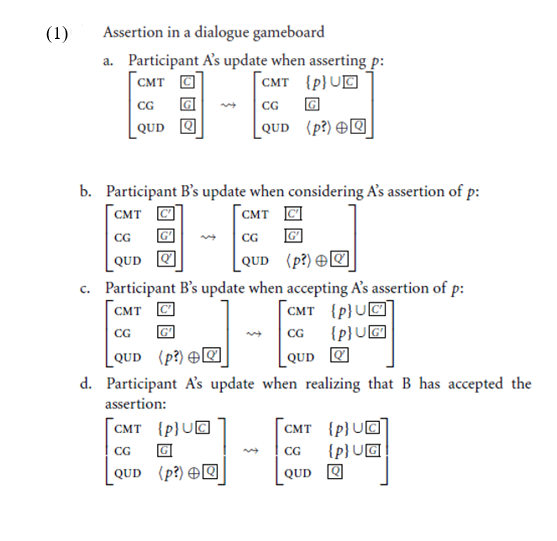

With those definitions in mind, we can model the dialogue gameboard as a feature structure, and describe dialogue moves as updates to that feature structure. Let us start with a detailed description of successful assertion. When a speaker A asserts p (34a), he puts p in his commitment set; he also puts the question whether p on the top of the qud, which signals that he considers that the question is open to discussion and that he is waiting for the addressee’s uptake. The addressee B may react by just refusing to consider A’s assertion. But if he is willing to consider it (34b), this amounts to putting the question whether p on the top of his own qud. B may then either accept A’s assertion of p or reject it – the issue then stays under discussion. If the assertion is accepted, this amounts to B putting p in his own set of commitments and removing whether p from his qud (34c);2 as a side effect, B now believes p to be common ground, since both participants are committed to it. Finally, when A realizes that B has accepted p, he considers the question whether p to be settled (and thus removes it from qud) and the proposition p to be common ground (34d).

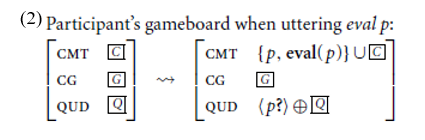

Our proposal for the role of evaluatives is as follows.When uttering eval p, the speaker puts the evaluative in his own set of commitments without putting it on the qud list. Accordingly, the evaluative is not under discussion, and cannot be rejected or accepted by the usual means. In addition, the main assertion can be accepted or rejected independently of the evaluative. The addressee is not committed either way, since the evaluative is not part of qud.

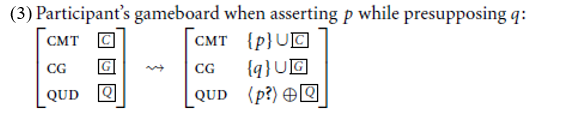

Note that this contrasts with the situation which holds when a participant utters a clause including a presupposition. When asserting a proposition p that presupposes q, the speaker acts as if q were common ground (3). Thus on the one hand there is something in common between evaluatives and presuppositions: neither are put under discussion; on the other hand, there is something in common between evaluatives and assertion: in both cases the speaker makes no claim as to the addressee’s information state, whereas a presupposition signals a belief about that information state. This explains why presupposing a proposition that one knows the addressee to believe to be false is uncooperative, while making an evaluative comment with the same content – or asserting that content – is not.

1 Notice that we do not propose to represent explicitly within the dialogue gameboard a record of the addressee’s commitments. While it is clear that discourse participants keep track of what their interlocutors are committed to in order to plan their future utterances, it is not clear that this information is used to constrain linguistic form. See Gunlogson (2001); Beyssade and Marandin (2006) for relevant discussion.

2 Notice that on this view some dialogue gameboard updates may have no linguistic reflex, or even no reflex at all. Thus accepting an assertion may consist in an utterance (e.g. yes), a non-linguistic event (e.g. a nod) or no reaction at all. The decomposition of assertion in elementary gameboard updates is taken to reflect the fact that signaling explicitly the acceptance of an assertion is the rule rather than the exception.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)