Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

The pronunciation of Maori words in New Zealand English

المؤلف:

Laurie Bauer and Paul Warren

المصدر:

A Handbook Of Varieties Of English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

597-33

2024-04-20

1059

The pronunciation of Maori words in New Zealand English

A political language issue in New Zealand is the pronunciation of Maori words when they are used in English. Broadly, we can sketch two extreme positions: (i) an assimilationist position, according to which all Maori words are pronounced as English, and (ii) a nativist position, according to which all Maori words are pronounced as near to the original Maori pronunciation as possible. There are, of course, intermediate positions in actual usage. Some of the variation is caused by the fact that the original Maori pronunciation may not be easily determinable. Not only is vowel length sometimes variable even in traditional Maori, in some cases the etymology of place names may be in dispute within the Maori community (Paraparaumu provides an instance of this, where it is not clear whether the final umu is to be interpreted as ‘earth oven’ or not).

Where vowels are concerned, the major difficulty in pronouncing Maori words with their original values is that vowel length (usually marked by macrons in Maori orthography, as in Māori) is rarely marked on public notices. Not only can this affect the way in which the particular vowel is pronounced, it can affect stress placement as well, since stress in Maori words is derivable from moraic structure. The reluctance to use macrons in public documents may simply be a typographical problem (even today with computer fonts easily available, very few newspapers or journals appear to have fonts with macrons available to them), but in the past has also been supported by the sentiments of Maori speakers who have found the macron unaesthetic. There may be good linguistic reasons for this, though they remain largely unexplored. The point is that although all vowels show contrastive length in Maori, long may be pronounced as short and short may be pronounced as long in English. Since Maori has no reduced vowels while English tends to reduce vowels in unstressed syllables (though this is less true of New Zealand English than it is of RP), almost any Maori vowel may be reduced under appropriate prosodic conditions. Where toponyms are concerned, there has also been a very strong Pakeha tradition towards abbreviating the longer names (a tradition which does not appear to spread to English names). For example, Paraparaumu is frequently called Paraparam, the Waimakariri river is called the Waimak, Wainuiomata is frequently called Wainui. While there is also a tradition for the abbreviation of names within Maori itself, and the two traditions may support each other to some extent, they appear to be largely distinct traditions with different outcomes. Pakeha abbreviations of toponyms are frowned upon within the nativist position on the pronunciation of Maori.

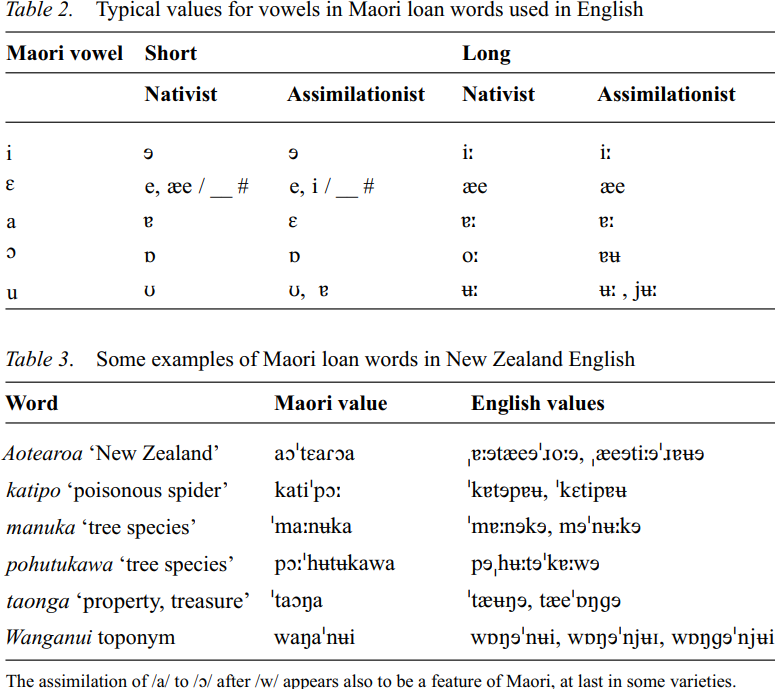

Table 2 shows a range of possible pronunciations of the individual vowels of Maori, assuming that length has been correctly transferred to English. Table 3 provides some typical examples with a range of possible pronunciations, going from most nativist to most assimilationist. Maori pronunciations are also heard, and these may be considered to provide instances of code-shifting.

Maori diphthongs and vowel sequences do not transfer well to English. Maori /aε/ and /ɔε/ are merged with Maori /ai/ and /ɔi/ respectively as English /ae/ and /oe/. Similarly Maori /aɔ/ and /au/ may not be distinguished in English. Maori /au/, which in modern Maori is pronounced with a very central and raised allophone of /a/, is replaced by  in nativist pronunciations (where it may merge with Maori /ɔu/), but by

in nativist pronunciations (where it may merge with Maori /ɔu/), but by  in assimilationist pronunciations. Because of the NEAR-SQUARE merger in New Zealand English, Maori /ia/ and /εa/ are not distinguished in English. Maori /εu/ is often transferred into English as

in assimilationist pronunciations. Because of the NEAR-SQUARE merger in New Zealand English, Maori /ia/ and /εa/ are not distinguished in English. Maori /εu/ is often transferred into English as  (presumably on the basis of the orthography). Vowel sequences are transferred to English as sequences of the nearest appropriate vowel, but often involve vowel reduction in English which would not be used in Maori.

(presumably on the basis of the orthography). Vowel sequences are transferred to English as sequences of the nearest appropriate vowel, but often involve vowel reduction in English which would not be used in Maori.

Most Maori consonants have obvious and fixed correspondents in English, although this has not always been so. Some early borrowings show English /b, d, g/ for Maori (unaspirated) /p, t, k/ and occasionally English /d/ for Maori tapped /r/: for example English biddybid is from Maori piripiri. The phonetic qualities of the voiceless plosives and /r/ are now modified to fit with English habits. However, Maori /ŋ/ is variably reproduced in English as /ŋ/ or as /ŋg/, especially when morpheme internal. Word-initial /ŋ/ is always replaced in English by /n/. The Maori /f/, written as <wh>, has variable realizations in English. This is partly due to the orthography, partly due to variation in the relevant sounds in both English and Maori: [M] is now rare as a rendering of graphic in English, and the /f/ pronunciation is an attempt at standardising variants as disparate as [f], [M], [ɸ] , [ʔw] . The toponym Whangarei may be pronounced /fæŋɐræe, fɐŋɘræe, wɒŋɘræe, wɒŋgɘræe/.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)