Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Major class features

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

47-3

24-3-2022

4175

Major class features

One of the most intuitive distinctions which feature theory needs to capture is that between consonants and vowels. There are three features, the so-called major class features, which provide a rough first grouping of sounds into functional types that includes the consonant/vowel distinction.

syllabic (syl): forms a syllable peak (and thus can be stressed).

sonorant (son): sounds produced with a vocal tract configuration in which spontaneous voicing is possible.

consonantal (cons): sounds produced with a major obstruction in the oral cavity.

The feature [syllabic] is, unfortunately, simultaneously one of the most important features and one of the hardest to define physically. It corresponds intuitively to the notion “consonant” (where [h], [ j], [m], [s], [t] are “consonants”) versus “vowel” (such as [a], [i]): indeed the only difference between the vowels [i, u] and the corresponding glides [ j, w] is that [i, u] are [+syllabic] and [ j, w] are [-syllabic]. The feature [syllabic] goes beyond the intuitive vowel/consonant split. English has syllabic sonorants, such as [r̩ ], [l̩], [n̩ ]. The main distinction between the English words (American English pronunciation) ear [ɪr] and your [ jr̩ ] resides in which segments are [+syllabic] versus [-syllabic]. In ear, the vowel [ɪ] is [+syllabic] and [r] is [-syllabic], whereas in your, [ j] is [-syllabic] and [r̩ ] is [+syllabic]. The words eel [il] and the reduced form of you’ll [ jl̩] for many speakers of American English similarly differ in that [i] is the peak of the syllable (is [+syllabic]) in eel, but [l̩] is the syllable peak in you’ll.

Other languages have syllabic sonorants which phonemically contrast with nonsyllabic sonorants, such as Serbo-Croatian which contrasts syllabic [r̩ ] with nonsyllabic [r] (cf. groze ‘fear (gen)’ versus gr̩ oce ‘little throat’). Swahili distinguishes [mbuni] ‘ostrich’ and [m̩ buni] ‘coffee plant’ in the fact that [m̩ buni] is a three-syllable word and [m̩ ] is the peak (the only segment) of that first syllable, but [mbuni] is a two-syllable word, whose first syllable peak is [u]. Although such segments may be thought of as “consonants” in one intuitive sense of the concept, they have the feature value [+syllabic]. This is a reminder that there is a difference between popular concepts about language and technical terms. “Consonant” is not strictly speaking a technical concept of phonological theory, even though it is a term quite frequently used by phonologists – almost always with the meaning “nonpeak” in the syllable, i.e. a [-syllabic] segment.

The definition of [sonorant] could be changed so that glottal configuration is also included, then the laryngeals would be [–sonorant]. There is little compelling evidence to show whether this would be correct; later, we discuss how to go about finding such evidence for revising feature definitions.

The feature [sonorant] captures the distinction between segments such as vowels and liquids where the constriction in the vocal tract is small enough that no special effort is required to maintain voicing, as opposed to sounds such as stops and fricatives which have enough constriction that effort is needed to maintain voicing. In an oral stop, air cannot flow through the vocal tract at all, so oral stops are [–sonorant]. In a fricative, even though there is some airflow, there is so much constriction that pressure builds up, with the result that spontaneous voicing is not possible, thus fricatives are [–sonorant]. In a vowel or glide, the vocal tract is only minimally constricted so air can flow without impedance: vowels and glides are therefore [+sonorant]. A nasal consonant like [n] has a complete obstruction of airflow through the oral cavity, but nevertheless the nasal passages are open which allows free flow of air. Air pressure does not build up during the production of nasals, so nasals are [+sonorant]. In the liquid [l], there is a complete obstruction formed by the tip of the tongue with the alveolar ridge, but nevertheless air flows freely over the sides of the tongue so [l] is [+sonorant].

The question whether r is [+sonorant] or [-sonorant] has no simple answer, since many phonetically different segments are transcribed as r; some are [-sonorant] and some are [+sonorant], depending on their phonetic properties. The so-called fricative r of Czech (spelled ř) has a considerable constriction, so it is [-sonorant], but the English type [ɹ] is a sonorant since there is very little constriction. In other languages there may be more constriction, but it is so brief that it does not allow significant buildup of air pressure (this would be the case with “tapped” r’s). Even though spontaneous voicing is impossible for the laryngeal consonants [h, ʔ] because they are formed by positioning the vocal folds so that voicing is precluded, they are [+sonorant] since they have no constriction above the glottis, which is the essential property defining [+sonorant].

The feature [consonantal] is very similar to the feature [sonorant], but specifically addresses the question of whether there is any major constriction in the oral cavity. This feature groups together obstruents, liquids and nasals which are [+consonantal], versus vowels, glides, and laryngeals ([h, ʔ]) which are [-consonantal]. Vowels and glides have a minor obstruction in the vocal tract, compared to that formed by a fricative or a stop. Glottal stop is formed with an obstruction at the glottis, but none in the vocal tract, hence it is [-consonantal]. In nasals and liquids, there is an obstruction in the oral cavity, even though the overall constriction of the whole vocal tract is not high enough to prevent spontaneous voicing. Recent research indicates that this feature may not be necessary, since its function is usually covered as well or better by other features.

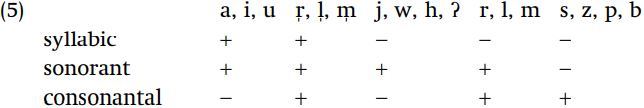

The most important phonological use of features is that they identify classes of segments in rules. All speech sounds can be analyzed in terms of their values for the set of distinctive features, and the set of segments that have a particular value for some feature (or set of feature values) is a natural class. Thus the segments [a i r̩ m̩ ] are members of the [+syllabic] class, and [ j h ʔ rmsp] are members of the [-syllabic] class; [a r̩ j ʔ r m] are in the [+sonorant] class and [s z p b] are in the [-sonorant] class; [aiwh ʔ] are in the [-consonantal] class and [r̩ m̩ r m s p] are in the [+consonantal] class. Natural classes can be defined in terms of conjunctions of features, such as [+consonantal, -syllabic], which refers to the set of segments which are simultaneously [+consonantal] and [-syllabic].

When referring to segments defined by a combination of features, the features are written in a single set of brackets – [+cons, -syl] refers to a single segment which is both +consonantal and -syllabic, while [+cons] [–syl] refers to a sequence of segments, the first being +consonantal and the second being -syllabic.

Accordingly, the three major class features combine to define five maximally differentiated classes, exemplified by the following segment groups.

Further classes are definable by omitting specifications of one or more of these features: for example, the class [-syllabic, +sonorant] includes {j, w, h, ʔ, r, l, m}.

One thing to note is that all [+syllabic] segments, i.e. all syllable peaks, are also [+sonorant]. It is unclear whether there are syllabic obstruents, i.e. [s̩ ], [k̩ ]. It has been claimed that such things exist in certain dialects of Berber, but their interpretation remains controversial, since the principles for detection of syllables are controversial. Another gap is the combination [-sonorant, -consonantal], which would be a physical impossibility. A [-sonorant] segment would require a major obstruction in the vocal tract, but the specification [-consonantal] entails that the obstruction could not be in the oral cavity. The only other possibility would be constriction of the nasal passages, and nostrils are not sufficiently constrictable.

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

الاكثر قراءة في Phonology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)