The rod cells

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 36

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 36

2024-04-06

2024-04-06

2229

2229

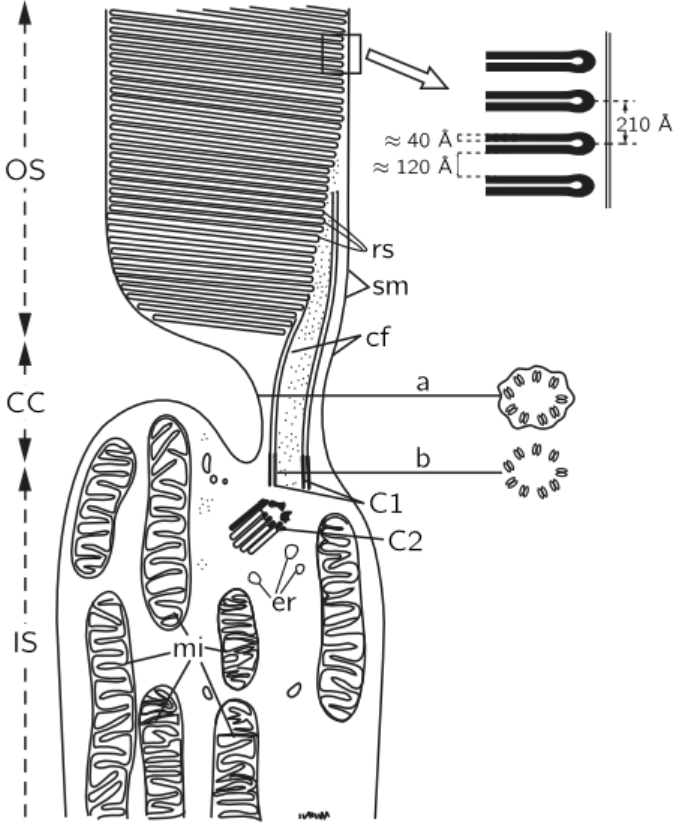

Fig. 36–5. Electron micrograph of a rod cell.

Let us now examine in more detail what happens in the rod cells. Figure 36–5 shows an electron micrograph of the middle of a rod cell (the rod cell keeps going up out of the field). There is layer after layer of plane structures, shown magnified at the right, which contain the substance rhodopsin (visual purple), the dye, or pigment, which produces the effects of vision in the rods. The rhodopsin, which is the pigment, is a big protein which contains a special group called retinene, which can be taken off the protein, and which is, undoubtedly, the main cause of the absorption of light. We do not understand the reason for the planes, but it is very likely that there is some reason for holding all the rhodopsin molecules parallel. The chemistry of the thing has been worked out to a large extent, but there might be some physics to it. It may be that all of the molecules are arranged in some kind of a row so that when one is excited an electron which is generated, say, may run all the way down to some place at the end to get the signal out, or something. This subject is very important, and has not been worked out. It is a field in which both biochemistry and solid state physics, or something like it, will ultimately be used.

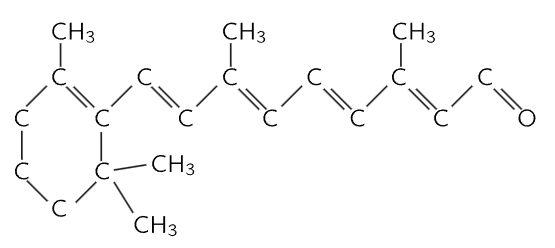

Fig. 36–6. The structure of retinene.

This kind of a structure, with layers, appears in other circumstances where light is important, for example in the chloroplast in plants, where the light causes photosynthesis. If we magnify those, we find the same thing with almost the same kind of layers, but there we have chlorophyll, of course, instead of retinene. The chemical form of retinene is shown in Fig. 36–6. It has a series of alternate double bonds along the side chain, which is characteristic of nearly all strongly absorbing organic substances, like chlorophyll, blood, and so on. This substance is impossible for human beings to manufacture in their own cells—we have to eat it. So we eat it in the form of a special substance, which is exactly the same as retinene except that there is a hydrogen tied on the right end; it is called vitamin A, and if we do not eat enough of it, we do not get a supply of retinene, and the eye becomes what we call night blind, because there is then not enough pigment in the rhodopsin to see with the rods at night.

The reason why such a series of double bonds absorbs light very strongly is also known. We may just give a hint: The alternating series of double bonds is called a conjugated double bond; a double bond means that there is an extra electron there, and this extra electron is easily shifted to the right or left. When light strikes this molecule, the electron of each double bond is shifted over by one step. All the electrons in the whole chain shift, like a string of dominoes falling over, and though each one moves only a little distance (we would expect that, in a single atom, we could move the electron only a little distance), the net effect is the same as though the one at the end was moved over to the other end! It is the same as though one electron went the whole distance back and forth, and so, in this manner, we get a much stronger absorption under the influence of the electric field, than if we could only move the electron a distance which is associated with one atom. So, since it is easy to move the electrons back and forth, retinene absorbs light very strongly; that is the machinery of the physical-chemical end of it.

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء الحيوية

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء الحيوية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة