النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية|

Read More

Date: 20-10-2016

Date: 17-10-2016

Date: 29-10-2015

|

The World Biomes at Present

As a result of continental drift, the United States is currently located almost exclusively in the north temperate zone and receives much of its weather from the Pacific and Arctic Oceans in winter and from the Pacific Ocean and tropical Atlantic Ocean in summer. Much of Alaska is situated in the polar zone, while Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and Guam lie in tropical waters.

MOIST TEMPERATE BIOMES

Temperate Rainforests. The northwest coast of the United States is formed by a series of mountain ranges that force the westerly winds from the Pacific Ocean to rise as soon as they come ashore. On the Olympic Peninsula in Washington, rain on the western side of the Olympic Mountains is often above 300 cm/yr. The rains are reliably present through autumn, winter, and spring, with only a brief period of summer dryness. Winters are mild and only rarely is there frost; summers are warm but not hot. These conditions extend from northern California to Alaska, but they end at the summit of the Coastal Range, about 200 km from the coast.

Plant life in the temperate rainforest biome is dominated by giant long-lived conifers. Coastal redwoods of California are up to 100 m tall, and Douglas fir, western hemlock, and western red cedar form a canopy that reaches 60 to 70 meters. The forests can attain old age with little disturbance: Hurricanes and tornadoes do not occur, and fires are rare. The stability of the forest and the daily fog result in a rich growth of epiphytic mosses, liverworts, and ferns; the ground is also covered with shrubs, herbs, and ferns (Fig. 1). Temperate rainforests, containing totally different species, also occur in southwest Chile, which has the same climate.

FIGURE 1: The Olympic National Park in Washington State encompasses a superb temperate rainforest, one of the moist temperate biomes. Abundant rain occurs almost every day, temperatures are never extremely hot or cold, and disturbances are rare or nonexistent. The ecosystems in this biome are very stable and are dominated by A-selected species; weedy, r-selected species are rare. (David Muench Photography)

Drier Montane and Subalpine Forests. As the westerly winds continue inland, they are drier and shed less rain on the Cascade Mountains and the Sierra Nevadas, then even less on the Rocky Mountains; each range feels the rain shadow effect of the preceding mountains. Montane forests occur at the bases of these mountains, subalpine forests at higher elevations (Fig. 2). The first inland range in California is the Sierra Nevada; its lower elevations hold a montane forest of ponderosa pine, and some oaks from the valley floor may extend some distance up the slopes. At higher elevations is a mixed conifer forest, one containing many species of conifers: ponderosa pine, Douglas fir, white fir, incense cedar, and sugar pine. The most famous residents are the giant sequoia, the largest organisms in the world, much more massive than whales, being 80 m tall, up to 10 m in circumference, and weighing over 400 metric tons when dry. At the higher elevations are subalpine forests of lodgepole pine, whitebark pine, and mountain hemlock. These form open stands and give way to alpine meadows at their upper boundaries (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 2: This is a drier montane forest (moist temperate biome), which may become warm in July and August and have several weeks without much precipitation. The forest is open and sunny and contains few epiphytes. Pines, firs, and cedars are abundant and dominant in the north; they are joined by oaks in the south.

FIGURE 3: High elevations have increased precipitation and winds and decreased temperature and growing season. The montane forest gives way to alpine meadows. Many areas are flat enough that small bogs and marshes form, being rich in sedges. Rocky Mountain National Park. (David Muench Photography)

The Rocky Mountains are our most massive mountain range, extending in a broad band from Alaska south through Canada, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, and Mexico. Being the third range from the coast, it is driest, receiving as little as 40 cm of rain per year; the southern rockies are especially dry and warm. The subalpine forest contains Engelman spruce over the entire length of the range, but in the north other trees are alpine larch and whitebark pine; in the south, varieties of bristlecone pine are part of the subalpine forest. The montane forests typically contain Douglas fir in their higher elevations, ponderosa pine in lower ones. The montane forests on the Rocky Mountains are frequently subjected to fire, as often as every 5 years under natural conditions. Ponderosa pine is well-adapted to fire and survives it easily. Other plants are killed, and fires create open grassy areas around the pines.

In drier montane and subalpine forests, soil is shallow, rocky, and very well drained; it tends to be acidic. Water stress in summer is not uncommon, due both to sparse rain and to rapid runoff through porous soils on steep slopes (Fig. 4). Much of the available moisture comes as the melting of winter snow.

FIGURE 4: Much of the dryness of the Rocky Mountains is due to edaphic (soil) conditions as well as to climate. Because these mountains are still very young and steep, soil formation is slow and soil erosion is rapid. The thin, rocky soil is not very effective at holding the moisture that does fall, and in summer, plants often have little soil moisture available.

In the eastern United States, the Adirondacks and Appalachians are tall enough to support montane and subalpine forests. In the Adirondacks, a spruce/fir subalpine forest extends down to 760 m and contains balsam fir (Fig. 5). In the warmer southern climate, the lower limit for subalpine forest is higher: 990 m in the Appalachians and 1400 in the Smoky Mountains. Above these elevations are stands of red and black spruce and Fraser's fir.

FIGURE 5: In contrast to the Rocky Mountains, the Appalachians are ancient, having arisen during the formation of Laurasia prior to the formation of Pangaea. They have since been eroded extensively so that they are low and gently sloped and have a thick, rich soil. The higher elevations support subalpine forests of conifers, and the lower elevations have montane forests of hardwoods (dicots). (Jim Tuten/Earth Scenes)

Temperate Deciduous Forests. The climate that produces the temperate deciduous forest biome is one with cold winters and warm but not hot summers and relatively high precipitation in all seasons. Whereas the drier montane and subalpine forests of the Rocky Mountains have streams with running water restricted mostly to springtime when snowpack is melting, the northeastern temperate deciduous forest has streams that flow year round. Much of the precipitation in the northeastern region is derived from summer weather systems that move northward out of the central Atlantic Ocean or from winter storms that blow southward from Arctic seas.

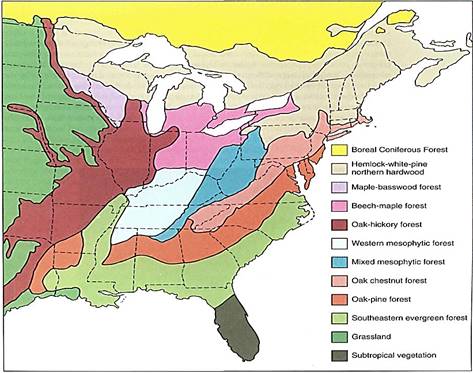

Temperate deciduous forest in the United States occupies lower, warmer regions, whereas higher, cooler elevations support the subalpine vegetation of the Appalachians and Adirondacks (Fig. 6). Dominant trees vary geographically, but tall, broadleaf deciduous trees such as maple and oak are frequent everywhere, maples being more common in the north and oak in the south. Intermixed and forming a subcanopy are dogwood, hop hornbeam, and blue beech. The shrub layer is sparse because of the heavy shade provided by broadleaf dominants, but witch hazel, spicebush, and gooseberry are common. The ground layer is covered with /--selected herbs that thrive during the spring warmth just before trees leaf out. Such a spring sunny period does not occur in the evergreen forests.

FIGURE 6: The temperate deciduous forest (moist temperate biome) is an extensive and complex biome in the eastern United States consisting of many subdivisions. This is an area of low, nonmountainous topography with cold, wet winters and warm, rainy summers. Soils are deep.

The foliage of these angiosperm trees contains fewer defensive chemicals than do the needles and scale leaves of a conifer. There may be 3 to 4 metric tons of broadleaf foliage per hectare in a temperate deciduous forest, and as much as 5% is consumed by herbivores; the rest is abscised in autumn and decays quickly in the humid conditions produced by frequent rain. A thick layer of litter does not accumulate.

The forest is not uniform across its entire breadth. The geographic extent of temperate deciduous forest biome contains numerous soil types, various altitudes, and gradients of temperature and precipitation. As many as nine subdivisions have been recognized, such as oak/hickory forest (Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas), oak/chestnut forest (Pennsylvania, the Virginias), oak/pine forest (east Texas, northwest Louisiana, and northern parts of Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and the Carolinas), beech/maple forest (Michigan, Indiana, Ohio), maple/basswood forest (Wisconsin, Minnesota), and hemlock/white pine forest (northern Wisconsin to New York).

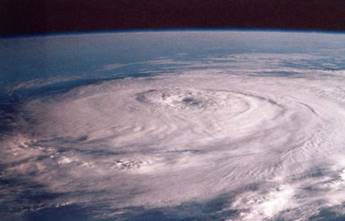

The forests in these areas have rich species diversity, and their considerable vertical structure provides a diversity of habitats for animals and fungi. Much animal life is located above or below ground, but not at its surface. Few birds nest on the ground; most make their nests on branches or in holes in the trunk. Small mammals may burrow, but many are arboreal. As in the coniferous forest at higher elevations here and in the inland western mountains, strong climatic differences exist between summer and winter, accented by the deciduous nature of the broadleaf forest. Autumn leaf fall ends the feeding period for aerial insect leaf-eaters but initiates the season for decomposers and insect herbivores of the litter zone. Many birds emigrate to wintering grounds, but other species may immigrate from farther north. Disturbance is not common; fires are rare and hurricanes that enter the regions usually lose destructive power quickly and change into widespread weaker storms (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7: Hurricanes move westward in the Atlantic but turn north-northeastward as they approach land. Many enter land between Texas and Florida, then move up the Mississippi River Valley or just east of it. The winds lose their hurricane force immediately and change into a giant storm system that supplies summer rainfall. The photograph shows Hurricane Elena photographed from space. (NASA)

Southeastern Evergreen Forests. This biome shows the powerful effect that disturbance and soil type can exert. The southeastern evergreen forest biome occurs at the southern edge of the oak/pine component of the temperate deciduous forest, along the northern portions of the Gulf States, the top of Florida, and the coast of the Carolinas. Its climate is similar to that of the inland region except that winters are warmer; frosts occur but the ground does not freeze. Precipitation is higher than in inland temperate deciduous forest areas, but the soil is so sandy and porous that rainwater percolates downward rapidly and runs off into streams. Shortly after a rain, the soil is dry. The region has a definite dry aspect to it.

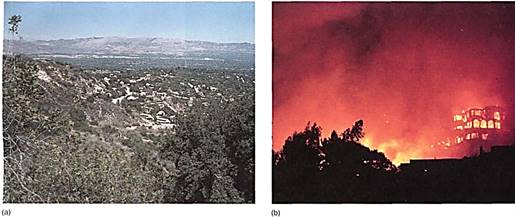

fn addition to rapid drainage, the biome is shaped by frequent fires; lightning initiates fires that burn rapidly through the litter of fallen pine needles that decompose only slowly (Figs. 8). As a result of fire disturbance and soil conditions, the forest consists almost purely of fire-adapted longleaf pine with occasional oaks. The fact that fire rather than climate is the primary biome determinant has been proven by fire prevention: Repeatedly suppressing fire lets broadleaf seedlings survive and quickly changes the forest from pines to oaks, hickories, beeches, and evergreen magnolias.

FIGURE 8 : Fast, low, cool fires burn frequently through southeastern evergreen forests, one of the moist temperate biomes. This kills nonadapted species but leaves pines and cabbage palms: Without fires, seedlings of broadleaf trees would soon overtop the pines and make the forest floor too shaded for pine seedlings; within less than 100 years it could convert to an oak/beech forest. Notice that the flames are too low to reach the needles of the pine trees. (Dale Jackson/Visuals Unlimited)

DRY TEMPERATE BIOMES

Grasslands. The entire central plains of North America, extending from the Texas coast to and beyond the Canadian border is—or more accurately, was—grassland, often referred to as prairie. This part of North America has no mountains, being too far from the various continental collision zones; it is remarkably flat, with at most low, rolling hills. It is characterized climatically as drier than the forests discussed so far, being located in rain shadows of the prevailing westerlies but out of reach of many Atlantic weather systems. Rain is only about 85 cm/yr. Seasons vary from bitterly cold winters, especially in the north, to very hot summers. Climate and vegetation factors have produced some of the richest soil in existence anywhere. Rainfall is sufficient to promote reasonably rapid weathering of rock, but it is not so great as to leach away valuable elements. Grasses produce abundant foliage that, rather than abscising and falling to the soil, is eaten by herbivores, often large mammals such as cattle or, in the past, buffalo. Vegetable matter is returned to the soil as manure that decomposes rapidly, enriching the soil and increasing its water- holding capacity. Because of the lack of trees, except along rivers, no treetop habitats are available for animals like squirrels. All small mammals burrow and birds nest on the ground.

Because the soil is so rich, almost all the grasslands have been converted to farms; virtually nothing remains of the original biome. Efforts are being made to re-establish grassland prairie by removing all domesticated plants and seeding in grasses and other species known to have occurred originally, such as composites, mints, and legumes (Fig. 9). It is still too early to tell how successful these reconstruction efforts will be, but many fear that the plots are too small (a few hectares) and should instead be extensive enough to support herds of buffalo if the full ecosystem is to be restored.

FIGURE 9: Many groups are undertaking efforts to reestablish natural prairies. Native grasses are planted and non-native species weeded out. The animal communities must be re-established also to truly recreate the biome and make it self-perpetuating. Extensive acreage would be required to supply enough primary consumers to support the secondary consumers. (Pat Armstrong/ Visuals Unlimited)

It is not known for certain what the critical factors were that caused this region to be grassland as opposed to forest. The buffalo may have been important; they roamed in unimaginable numbers, and tree seedlings would have been poorly adapted to survive their grazing (Fig. 10). Also, Indians set prairies afire periodically, which caused the grasses to grow especially luxuriantly the following year, providing better feed for buffalo; seedlings of tree species were killed by the fire. A recent hypothesis is that grasses support a type of mycorrhizal fungus that outcompetes and eliminates the type of fungus necessary for forest trees.

Extensive grasslands occur between the Cascade Mountains and Rocky Mountains, the result of the Cascade's rain shadow. These extend from northern Washington south through Oregon and Nevada. Much of them remain, but they are grazed; large parts have been cleared and used for irrigated farms.

FIGURE 10: Large mammalian herbivores such as buffalo, deer, moose, and elk are important factors in their ecosystems. Grasses have basal meristems on their leaves and the shoot apical meristems are low, so grasses can be grazed without being killed. Grazing of shrubs and tree saplings destroys the leaves and the shoot apical meristems, so grazing tends to maintain a prairie as grassland, free of trees. But if too many cattle are fenced into an area, they overgraze it, killing even the grasses by eating leaves so quickly that no photosynthesis can occur. In this overgrazed pasture, the oaks and cacti have a selective advantage because their tough, bitter leaves or spines deter grazing.

Shrublands and Woodlands. A woodland is similar to a forest except that trees are widely spaced and do not form a closed canopy. If grass grows between the trees, the biome is known as a savanna instead (Fig. 11). Shrublands are similar except that trees are replaced by shrubs. Woodlands and shrublands often occur as the transition between a moist forest and dry grassland or between grassland and desert. Soils often have high clay content.

FIGURE 11: If trees are widely spaced and grass grows between them, it is a woodland biome, a type of dry temperate biome. These are often called parklands in the United States, savannas elsewhere. This is a transition biome, representing the interface between a forest and a grassland, but it is not just the mixing of the two. This is especially obvious when animal species are considered: Many birds nest in the trees but feed in the grasslands; these birds cannot live in pure forest or pure grassland. (David Muench Photography)

The chaparral in California is a well-known shrubland (Fig. 12a). Its climate consists of a rainy, mild winter followed by a dry, hot summer; drought occurs every year. Much of the California chaparral is dominated by short shrubs, I to 3 m tall, but at higher elevations manzanita, buckthorn, and scrub oak occur. Many plants have dimorphic root systems: Some roots spread extensively just below the soil surface, but a tap root system reaches great depths. The two together allow the plants to gather water from the deep, constant water table and from brief rains that penetrate only a few centimeters into the soil.

Fires occur frequently in California chaparral and are always in the news because of the houses they destroy. Low rainfall allows dry litter to accumulate without decomposing, and dead shrubs persist upright as dry sticks. An area typically burns every 30 to 40 years, with fires most frequent in summer. Winter rains cause flooding, erosion, and mudslides after a fire because no vegetation remains to hold soil in place. Although the shrubs and trees are fire-adapted and resprout quickly, the main new growth is by annual and perennial herbs. These are present before the fire as seeds, bulbs, rhizomes, or other protected structures, and after the burn they grow vigorously, free of shading by charred shrubs; release of minerals from the ash also enriches the soil (Fig. 12c). A few years after fire, larger shrubs dominate the biome again and herbs are suppressed, perhaps by allelopathy, perhaps by recovery of the herbivore population.

FIGURE 12: (a) This is California chaparral, one of the most famous shrubland biomes; such shrubland extends from California across the southwestern United States and northern Mexico into west Texas. Fire is an important disturbance that maintains this biome; it is being invaded by the large mammal Homo sapiens, which is protected by fire insurance policies. (John D. Cunningham/Visuals Unlimited) (b) The resinous leaves and accumulated dry litter cause frequent fires to be inevitable. (David]. Cross/ Peter Arnold, Inc.) (c) Seedlings of r-selected species flourish in the spaces opened by the burning of the dominant shrubs. These spots remain open only temporarily because the shrubs are fire-adapted and recover after a few years. By that time, the r-selected species will have grown and reproduced abundantly, limited mostly by their biotic potential. Before their population numbers can approach the carrying capacity of the open ecosystem, the growth of the shrubs begins to lower the carrying capacity of these smaller herbs. They are not lost from the ecosystem, however; their seeds either blow to newly burned sites or lie in the ground and sprout after the next fire. If fire were suppressed for many years, the seeds would finally die and these r-selected species would be lost from the biome. (Mike Andrews/Earth Scenes)

Farther east, drier climates and higher elevations result in pinyon/juniper woodland instead of chaparral shrubland. Rainfall is only 25 to 50 cm, and soils are rocky, shallow, and infertile. The vegetation is a savanna of pinyon pine—small, slow-growing trees with short needles—and juniper trees that may have the stature of large shrubs (Fig. 13). In Arizona and New Mexico, oaks may be important. Trees are widely spaced and between them is grassy vegetation; the species are bunch grasses that grow in clumps, not the mat-forming species of the central plains. Between the bunch grasses is bare soil. Sagebrush and bitterbush occur in the northern parts of the biome.

FIGURE 13: East from the California chaparral is the drier pinyon/juniper woodland, shown here in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico. Soils are rocky, thin, and poor, and in many areas chaparral grades into a desert or desert-grassland.

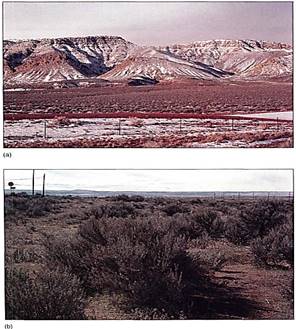

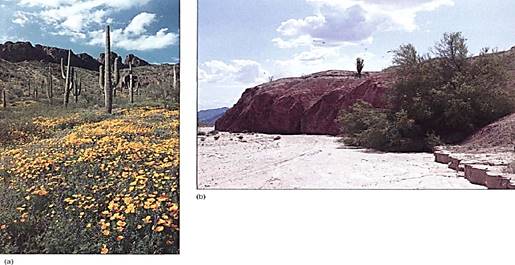

Desert. The driest regions of temperate areas are occupied by deserts, where rainfall is less than 25 cm/yr. Deserts are either cold or hot, based on their winter temperatures (Figs. 14 and 15). A hot desert has warm winter temperatures. In the United States, this climate occurs in rocky, mountainous areas of southern California, Arizona, New Mexico, and west Texas, but in other parts of the world it may occur on flat, sandy plains, as in the Sahara. Three separate and highly distinct deserts actually occur in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico: the Chihuahuan Desert in west Texas and New Mexico, the Sonoran Desert in Arizona and northwestern Mexico, and the Mohave Desert in southeastern California, southern Nevada, and northwestern Arizona.

Deserts soils are rocky and thin; what little soil occurs may blow away, leaving nothing but pebbles. Brief, intense thundershowers wash soil out of mountains and deposit it in large alluvial fans at valley entrances; fans often have the deepest soil and their own distinct vegetation. The most abundant plants in our hot deserts are creosote bush, bur sage, agaves, and prickly pear. Most perennial plants have one or several defenses against herbivores—chemicals and spines being the most common. Joshua tree, an arborescent lily, grows in the Mohave desert, and numerous other needle-leaf yuccas and agaves are abundant; cacti are ubiquitous. Deserts are highly patchy ecosystems, and slight variations in soil type, drainage, elevation, or covering vegetation can cause abrupt changes in vegetation. In valleys or mountains, slopes that face the equator intercept light almost perpendicularly and so are much warmer and drier than those that face away from the equator and are lighted obliquely. The hotter side has the richer xerophyte vegetation.

FIGURE 14: (a) The Great Basin Desert is a cold desert (in the winter only); it extends from near Las Vegas in the south well into Washington State, encompassing much of Nevada, eastern Oregon, and western Idaho. (b) The Great Basin Desert has two dominant plants, sagebrush (Artemesia tridentata) and a bunch grass (Bromus tectorum). Even the northern parts have cacti (Pediocactus and prickly pear), although they tend to be inconspicuous.

FIGURE 15: (a) For most North Americans, "desert" means Arizona and saguaro cactus (Carnegiea); actually, this species of cactus is quite atypical and seems to be poorly adapted; it may be in the process of becoming extinct. (b) Unlike streams and rivers in the eastern temperate deciduous forests, those of the western deserts have water in them only after a thunderstorm. At that time the water flows as a flash flood, moving at tremendous speed and carrying not just silt but entire boulders. Usually no water plants are associated with such streams, but their banks may contain trees such as this palo verde (Cercidium), whose deep roots tap the moisture that remains in the stream bed after the surface water has run off (b, Stephanie S. Ferguson)

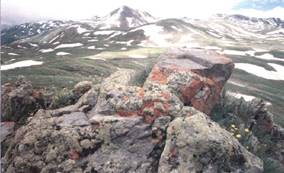

Alpine Tundra. The biome located above the highest point at which trees survive on a mountain, the timberline, is alpine tundra (Fig. 16). In the equatorial region, elevations as high as 4500 m can support tree growth, but in the cooler regions at 40 degrees N, elevations as low as 3500 m are too severe for trees. Alpine tundra is cold much of the year; with a short growing season limited by a late snow melt in spring and early snowfall in autumn. Soils are thin and have undergone little chemical weathering. Summer days can be surprisingly warm and clear, and many plants flourish in the brief summer. Nights are generally cold in all seasons, and severe, violent weather can occur at any time. The dominant forms of plant life are grasses, sedges, and herbs such as saxifrages, buttercups, and composites. Dwarf plants growing with densely packed stems and leaves are common and are known as cushion plants. Much of the alpine tundra land occurs as flat meadows with shallow alpine marshes.

It is not known for certain why trees do not grow above the tree line. Those near the highest elevation are short and typically have branches mostly on the side away from the wind; at slightly higher elevation, trees are extremely misshapen and gnarled, known by the German word krummholz; the forest is called an elfin forest. It is believed that blowing snow and ice abrade the trees' surfaces, permitting desiccation and death.

In North America, most alpine tundra biomes occur on the tall mountains in the west, but Mt. Washington in New Hampshire and Whiteface Mountain in New York are high enough to have regions of alpine tundra.

FIGURE 16: Plants in the Alpine tundra biome face short, cold growing seasons, and often snow is never gone from the shaded areas below cliffs. Soils are thin and ultraviolet light is intense. Mineral Point, Colorado. (David Muench Photography)

POLAR BIOMES

Arctic Tundra. Polar regions contain few significantly dry areas (Fig. 17). Precipitation, usually snow, may be low, but evaporation is also low, so moisture persists. In the extreme northern latitudes, the ground freezes to great depths during winter, and summer is too cool to melt anything more than the top few centimeters. Below this, soil is permanently frozen and is known as permafrost.

Like alpine tundra, arctic tundra has a short growing season of 3 months or less, and temperatures are cool, averaging only about 10°C. Freezing temperatures can occur on any day of the year. Arctic soils have a high clay content and are poor in nitrogen because nitrogen-fixing microbes are sparse. Permafrost prevents drainage when the soil surface melts in summer, so soils are waterlogged and marshy. Bogs, ponds, and shallow lakes are common.

Arctic tundra vegetation contains even more grasses and sedges than does alpine tundra, as well as many more mosses and lichens. Almost nothing is taller than 20 cm, even the dwarf willows and birches that occur. Many plants have underground storage tubers, bulbs, or succulent roots; more than 80% of a plant's biomass may be underground even during summer.

A FIGURE 17: rctic tundra, one of the polar biomes, is marshy and wet when not frozen solid; permafrost prevents water from seeping into the soil, and the area is so flat that runoff is slow. This is true only of the arctic tundra, an area that was on the trailing edge during the formation of Pangaea and has not collided with any other tectonic plate, so it has not undergone mountain building. Antarctic tundra is located on the Andes Mountains where drainage is excellent. Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, Alaska. (William E. Ferguson)

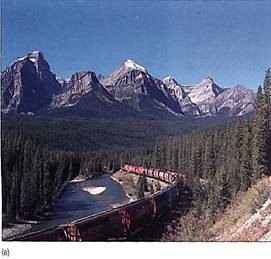

Boreal Coniferous Forests. Just south of arctic tundra is a broad band of forest, the boreal coniferous forest (Fig. 18). This forest occurs completely across Alaska and Canada and throughout northern Eurasia in Scandinavia and Russia. The Russian name for this biome is taiga, a term frequently used in the West. The boreal forest is an ancient biome, and its formation was strongly influenced by the diversification of division Coniferophyta just as the North American and Eurasian plates were breaking away from Pangaea and their northern parts were leaving the tropical zone and entering the north temperate, subarctic zone.

Boreal forest is almost exclusively coniferous; conifers appear to be adapted to this climate because they are evergreen and capable of photosynthesizing immediately whenever a sunny day occurs. Deciduous angiosperms would be limited to the short growing season, less than 4 months long. Conifers have drooping branches that shed snow easily; without this architecture, snow loads can easily break off limbs. Although the Coniferophyta contains many species, the boreal forest is not rich in diversity; it is not unusual for only two species to completely dominate thousands of square miles. Black spruce and white cedar may dominate western areas, while white spruce and balsam fir cover much of the eastern area. Shrubs are not abundant but include blueberries, cherries, and gooseberries. Herbs are also sparse. Not much disturbance occurs in the boreal forest; fire may occur in the south and insect plagues in northern parts. This biome does contain many large mammals such as moose, caribou, deer, grizzly bear, and timber wolves. Boreal forest is continuous with and grades into subalpine and montane forests that occur farther south. Many species may occur in both biomes.

FIGURE 18: (a) The boreal forest is gigantic, stretching not only along all of Canada and Alaska, but also across Scandinavia and northern Russia. Within any square kilometer, there may be thousands of individuals of the same species, so the wind pollination of conifers is highly efficient. Banff National Park, Canada. (Ken Cole/Earth Scenes) (b) Conifers dominate the boreal forest; flowering plants tend to be understory shrubs and herbs. Mt. Rainier National Park.

TROPICAL BIOMES

Most tropical biomes are characterized by a lack of freezing temperatures. On high mountains in the tropics, cool or cold nights and winters occur, but only at very high elevations is frost encountered. Under conditions of high rainfall, tropical rainforests develop, but the drier areas contain tropical grasslands and savannas.

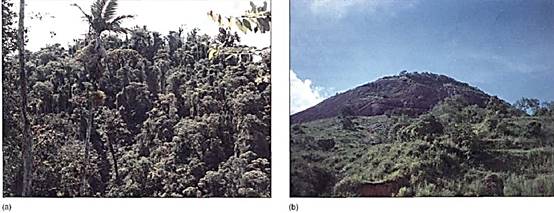

Tropical Rainforests. Tropical rainforests occur close to the equator; Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and Guam have extensive rain forests (Fig. 19 a). Precipitation is high, typically over 200 cm/yr and often as much as 1000 cm/yr (10 m—over 30 feet—of rain). Rains typically occur every day; the morning may be cool and fresh, but clouds develop rapidly and rain almost invariably falls by noon. After a rain, there are large clouds in a clear sky and bright sunlight; the temperature quickly rises and the relative humidity of the air is close to 100%.

High temperatures and moisture cause much more rapid soil transformation here than in other biomes. Many elements are leached from the soil, leaving behind just a matrix of aluminum and iron oxides. Humus decays rapidly, and there is little development of soil horizons. An extensive system of roots and mycorrhizae catch and recycle minerals as litter decays. Almost all available essential elements exist in the organisms, not in the soil (Fig. 19 b).

The dominant trees are angiosperms; virtually no conifers occur naturally in the tropical rainforest. The canopy is 30 to 40 m above ground level, but numerous large trees emerge above all others. A subcanopy may occur at about 10 to 25 m. Some trees have massive, gigantic trunks, but most are slender. In an undisturbed area where the canopy has remained intact for years, ground vegetation is minimal and it is easy to walk through the forest. Localized disturbances happen when a large tree dies and falls, creating a hole in the canopy. Suddenly, light is available on the forest floor, and herbs and shrubs proliferate. However, a tree soon grows up and fills the canopy, blocking light.

Virtually all small shrubs and herbs occur as epiphytes, located high in the canopy, nearer the light. Orchids, bromeliads, aroids, and cacti are common. Numerous vines are anchored in the soil, but their stems grow to the canopy, then branch and leaf out profusely. Leaves and roots can be separated by a narrow stem 50 m long.

Tropical rainforest is synonymous with species diversity. A single hectare may have well over 40 species of trees, often up to 100, and a single tree may harbor thousands of species of insects, fungi, and epiphytic plants. With such diversity, each hectare may have only one or two individuals of a particular species, especially of trees. No dominants occur. With such low population density for most species, wind pollination is not successful. All plants must be pollinated by animals, and being noticed by a pollinator can be difficult; many subcanopy species have brilliantly colored flowers that are easy to see in the dim light, and scents tend to be so strong that insects and birds find the flowers quickly. Large trees can undergo a massive flowering that no pollinator could possibly ignore (Fig. 20).

FIGURE 19 : (a) Unlike temperate rainforests, tropical rainforests (one of the tropical biomes) are never exposed to freezing conditions. Photosynthesis can occur throughout the year. Because leaves are not deciduous, their useful lifetime is not limited to just several summer months, but rather they can be effective for several years. On mountainous areas, landslides are a frequent disturbance, but in flat plains, ecosystems may be extremely stable. Panama. (b) Millions of acres of tropical rainforests are being cleared for farming every year; after the native plants have been cut and burned, the soil is temporarily rich from the mineral content of the ash. But this quickly leaches away because of the low clay content of the soil; after a year or two, crops fail and the farmers clear more land. Unfortunately, the forest cannot recover the abandoned fields; the trees are not adapted to the mineral-free soil and need to have a thick layer of humus.

FIGURE 20 : Tropical rainforest is a sea of green; small, inconspicuous flowers would never be noticed by pollinators unless they had strong fragrances. Many tree species undergo massive flowering, involving not only simultaneous opening of all flowers on one tree but also the flowering of all trees within an area. This is not controlled by photoperiod because day length changes too little near the equator. Instead, in some plants it is triggered by changes in air temperature or humidity associated with a rainstorm at the end of the dry season.

Tropical Grasslands and Savanna. Those areas of the tropics with lower rainfall develop as savannas (a few trees; Fig. 21) or grasslands (no trees). The best known savannas are in Africa, but they also occur in Brazil (the cerrados), Venezuela (the llanos), and Australia (Fig. 22). Under natural conditions, undisturbed by humans, the vegetation consists mostly of bunch grasses up to 1.5 to 2 m tall. Most of the trees are open, flat-topped, widely scattered legumes. The South American savannas do not have many large grazers, but those of Africa are famous—zebras, wildebeests, and giraffes. An unexpected but very important grazer is the termite; termites are abundant and build giant nests of soil particles and plant debris. They bring in large amounts of plant material, digest it, and add their fecal material to the termite mound. Colonies are so abundant and the mounds so large that termites are a major link in nutrient cycling.

FIGURE 21: Along coastlines in tropical areas, the low-lying, flat, sandy terrain receives relatively little rainfall, and the sandy soil allows what little rain there is to seep away quickly. Conditions are desert-like, except for very high humidity. There may be a coastal thorn-scrub biome, so named because the trees are short and most bear spines. Although the area is relatively open, walking is almost impossible because of the numerous sharp spines everywhere. Also, the heat and humidity drain away most devotion to plant study.

FIGURE 22 Tropical grassland is a tropical biome in which rainfall is not abundant enough to support forest or thorn-scrub. Unlike temperate grasslands, they have no cold winter, but rather three seasons: warm and wet, cool and dry, hot and dry. Otherwise, many aspects are similar to those of temperate grasslands. Mauna Kea, Hawaii. (Sydney Thomson/Earth Scenes)

|

|

|

|

حمية العقل.. نظام صحي لإطالة شباب دماغك

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

إيرباص تكشف عن نموذج تجريبي من نصف طائرة ونصف هليكوبتر

|

|

|

|

|

|

اختتام الأسبوع الثاني من الشهر الثالث للبرنامج المركزي لمنتسبي العتبة العباسية

|

|

|

|

راية قبة مرقد أبي الفضل العباس (عليه السلام) تتوسط جناح العتبة العباسية في معرض طهران

|

|

|

|

جامعة العميد وقسم الشؤون الفكرية يعقدان شراكة علمية حول مجلة (تسليم)

|

|

|

|

قسم الشؤون الفكريّة يفتتح باب التسجيل في دورات المواهب

|