علم الكيمياء

تاريخ الكيمياء والعلماء المشاهير

التحاضير والتجارب الكيميائية

المخاطر والوقاية في الكيمياء

اخرى

مقالات متنوعة في علم الكيمياء

كيمياء عامة

الكيمياء التحليلية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء التحليلية

التحليل النوعي والكمي

التحليل الآلي (الطيفي)

طرق الفصل والتنقية

الكيمياء الحياتية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الحياتية

الكاربوهيدرات

الاحماض الامينية والبروتينات

الانزيمات

الدهون

الاحماض النووية

الفيتامينات والمرافقات الانزيمية

الهرمونات

الكيمياء العضوية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الهايدروكاربونات

المركبات الوسطية وميكانيكيات التفاعلات العضوية

التشخيص العضوي

تجارب وتفاعلات في الكيمياء العضوية

الكيمياء الفيزيائية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الفيزيائية

الكيمياء الحرارية

حركية التفاعلات الكيميائية

الكيمياء الكهربائية

الكيمياء اللاعضوية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء اللاعضوية

الجدول الدوري وخواص العناصر

نظريات التآصر الكيميائي

كيمياء العناصر الانتقالية ومركباتها المعقدة

مواضيع اخرى في الكيمياء

كيمياء النانو

الكيمياء السريرية

الكيمياء الطبية والدوائية

كيمياء الاغذية والنواتج الطبيعية

الكيمياء الجنائية

الكيمياء الصناعية

البترو كيمياويات

الكيمياء الخضراء

كيمياء البيئة

كيمياء البوليمرات

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الصناعية

الكيمياء الاشعاعية والنووية

The molecular forces that hold proteins together

المؤلف:

..................

المصدر:

LibreTexts Project

الجزء والصفحة:

.................

16-12-2019

2003

The molecular forces that hold proteins together

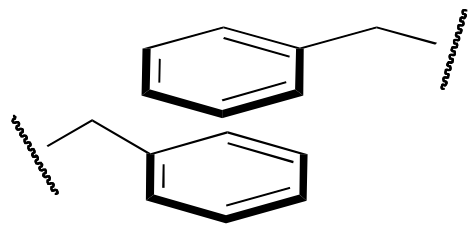

The question of exactly how a protein ‘finds’ its specific folded structure out of the vast number of possible folding patterns is still an active area of research. What is known, however, is that the forces that cause a protein to fold properly and to remain folded are the same basic noncovalent forces that we talked about in chapter 2: ion-ion, ion-dipole, dipole-dipole, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic (van der Waals) interactions. One interesting type of hydrophobic interaction is called ‘aromatic stacking’, and occurs when two or more planar aromatic rings on the side chains of phenylalanine, tryptophan, or tyrosine stack together like plates, thus maximizing surface area contact.

Hydrogen bonding networks are extensive within proteins, with both side chain and main chain atoms participating. Ionic interactions often play a role in protein structure, especially on the protein surface, as negatively charged residues such as aspartate interact with positively-charged groups on lysine or arginine.

One of the most important ideas to understand regarding tertiary structure is that a protein, when properly folded, is polar on the surface and nonpolar in the interior. It is the protein's surface that is in contact with water, and therefore the surface must be hydrophilic in order for the whole structure to be soluble. If you examine a three dimensional protein structure you will see many charged side chains (e.g. lysine, arginine, aspartate, glutamate) and hydrogen-bonding side chains (e.g. serine, threonine, glutamine, asparagine) exposed on the surface, in direct contact with water. Inside the protein, out of contact with the surrounding water, there tend to be many more hydrophobic residues such as alanine, valine, phenylalanine, etc. If a protein chain is caused to come unfolded (through exposure to heat, for example, or extremes of pH), it will usually lose its solubility and form solid precipitates, as the hydrophobic residues from the interior come into contact with water. You can see this phenomenon for yourself if you pour a little bit of vinegar (acetic acid) into milk. The solid clumps that form in the milk are proteins that have come unfolded due to the sudden acidification, and precipitated out of solution.

In recent years, scientists have become increasing interested in the proteins of so-called ‘thermophilic’ (heat-loving) microorganisms that thrive in hot water environments such as geothermal hot springs. While the proteins in most organisms (including humans) will rapidly unfold and precipitate out of solution when put in hot water, the proteins of thermophilic microbes remain completely stable, sometimes even in water that is just below the boiling point. In fact, these proteins typically only gain full biological activity when in appropriately hot water - at room-temperature they act is if they are ‘frozen’. Is the chemical structure of these thermostable proteins somehow unique and exotic? As it turns out, the answer to this question is ‘no’: the overall three-dimensional structures of thermostable proteins look very much like those of ‘normal’ proteins. The critical difference seems to be simply that thermostable proteins have more extensive networks of noncovalent interactions, particularly ion-ion interactions on their surface, that provides them with a greater stability to heat. Interestingly, the proteins of ‘psychrophilic’ (cold-loving) microbes isolated from pockets of water in arctic ice show the opposite characteristic: they have far fewer ion-ion interactions, which gives them greater flexibility in cold temperatures but leads to their rapid unfolding in room temperature water.

الاكثر قراءة في الاحماض الامينية والبروتينات

الاكثر قراءة في الاحماض الامينية والبروتينات

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)