Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Word structure revisited Limitations of the position class chart

المؤلف:

PAUL R. KROEGER

المصدر:

Analyzing Grammar An Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

P259-C13

2026-01-30

47

Word structure revisited

Limitations of the position class chart

We introduced the position class chart as a way of representing the morphological structure of a word. These charts are especially well suited to inflectional affixation where the affixes are arranged in paradigm sets occurring in a fixed order. Position class charts are often less successful as a way of displaying derivational morphology, for a variety of reasons.

First, we have noted that derivational morphology does not typically form paradigm sets such that only one affix in each set may occur in any given word. This means that each derivational affix in the language could potentially occupy its own position in the chart, which would require a large number of positions in many languages. Of course, there are often semantic reasons why two derivational affixes cannot occur together. For example, Manipuri (a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in north east India) has a pair of derivational modality markers which indicate the appropriateness of the time at which an action was performed: -həw ‘just in time ’and–khi‘ still (not done).’15 Since these two concepts are mutually contradictory, they cannot occur in the same verb form.

There are also categorial requirements which limit the co-occurrence of derivational affixes. For example, English has a number of nominalizing suffixes: -ment, -tion, -ity, etc. No two of these can occur next to each other, since they each attach to a base form which is not a noun and produce a stem which is a noun: e.g. creation, containment, but*creationment,*creationity. However, these affixes can co-occur if they are separated by some other affix which derives a stem of a different category: compart-ment al-iz-ation; constitu(te)-tion-al-ity; argu-ment-ativ-ity, etc. The possibility of co-occurrence shows that these nominalizing suffixes do not form a paradigm set.

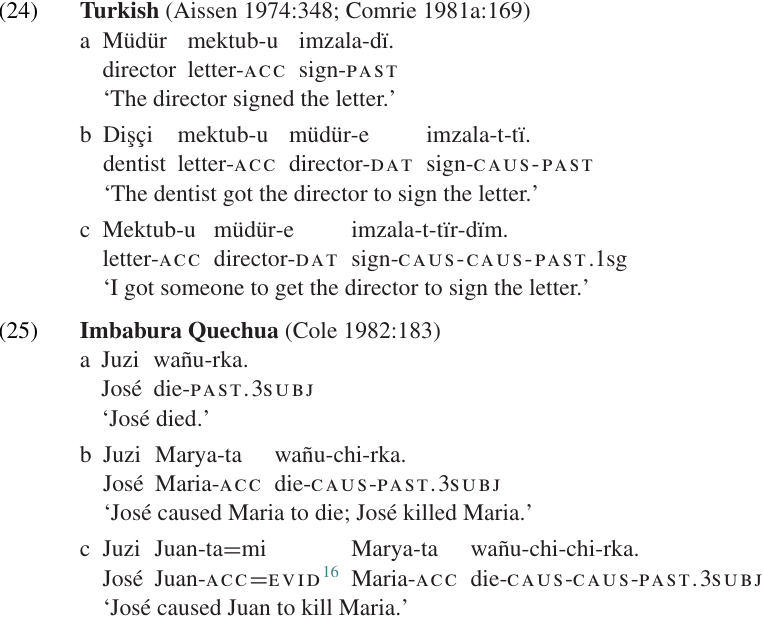

Second, derivational affixes can sometimes occur more than once within the same word. This is at least marginally possible in English, as in re-reinstate, re-reinvent, etc. (School principal to teacher: If you expel my nephew again, I will simply re-reinstate him.) Clearer examples are found in other languages. Manipuri has another modality marker, -lə ∼-rə, which indicates likelihood or probability. This suffix can be doubled or even tripled to indicate certainty: saw-rə-ni ‘is probably going to be angry’; saw-rə-rə-rə-ni ‘is definitely going to be angry.’ Double causatives are reported in a number of languages, including Turkish (24c) and Quechua (25c).

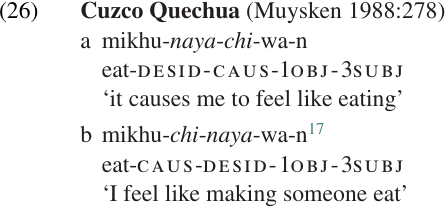

Third, the ordering of derivational affixes may be variable, with different semantic interpretations indicated by the differences in affix order. The causative and desiderative suffixes in Cuzco Quechua can appear in either order, as illustrated in (26).

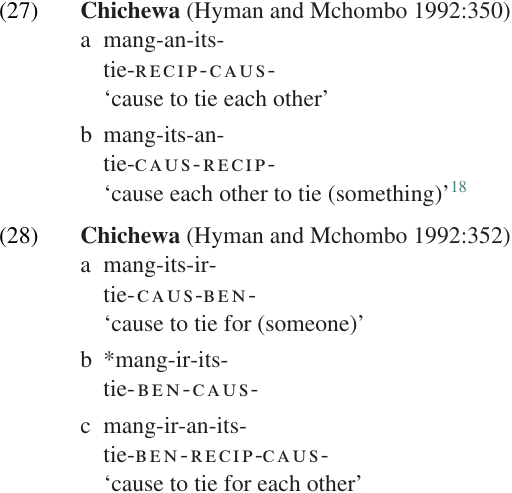

In Chichewa (Bantu, East Africa), the causative and reciprocal suffixes may appear in either order, as in (27). If the causative suffix appears next to the benefactive suffix, the causative must come first as in(28a). However, the benefactive suffix may precede the causative provided that some other affix intervenes, as in (28c). (Note that these examples involve only stems; all inflectional affixation, including subject agreement and tense, are omitted.)

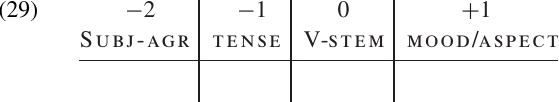

Examples like these are not uncommon, but they are difficult to deal with in any satisfying way in a position class chart. Multiple occurrences of the same affix, or variable ordering with respect to other affixes, would force us to assign a single affix to more than one position class. For these reasons, it is often more helpful to show only the inflectional categories in our position class chart. A possible chart for Chichewa verbs is presented in (29), without listing the inflectional affixes in each position.19 Note that the stem of the verb may consist of a single root, or of a root with one or more derivational affixes. The internal structure of the stem is, in general, “invisible” to the rest of the grammatical system.

15. All Manipuri examples are taken from Chelliah (1992).

16. =mi is an evidential clitic indicating first-hand information.

17. The experiencer triggers object agreement, rather than subject agreement, on stems formed with the desiderative suffix like (26b). Cole (1982:182) refers to such verbs as “impersonal verbs.”

18. Hyman and Mchombo (1992:360) point out that (27b) is actually ambiguous; it can also have the interpretation given for (27a). Example (27a), however, allows only one interpretation.

19. The chart in (29) does not include the “object agreement” position. Bresnan and Mchombo (1987) present evidence that the object marker in Chichewa is actually an incorporated pronoun. See Clitics for a discussion of a similar pattern in Muna.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)