The cognitive view: sociocognitive mechanisms in language acquisition

المؤلف:

Vyvyan Evans and Melanie Green

المؤلف:

Vyvyan Evans and Melanie Green

المصدر:

Cognitive Linguistics an Introduction

المصدر:

Cognitive Linguistics an Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

C4P136

الجزء والصفحة:

C4P136

2025-12-13

2025-12-13

49

49

The cognitive view: sociocognitive mechanisms in language acquisition

As we have seen, the fundamental assumption of cognitive approaches to grammar is the symbolic thesis: the claim that the language system consists of symbolic assemblies, or conventional pairings, of form and meaning. According to Michael Tomasello and his colleagues, when children acquire a language, what they are actually doing is acquiring constructions: linguistic units of varying sizes and increasing degrees of abstractness. As the complexity and abstractness of the units increases, linguistic creativity begins to emerge. According to this view, the creativity exhibited by young children in their early language happens because they are ‘constructing utterances out of various already mastered pieces of language of various shapes and sizes, and degrees of internal structure and abstraction – in ways appropriate to the exigencies of the current usage event’ (Tomasello 2003: 307). This view of language acquisition is called emergentism, and stands in direct opposition to nativism, the position adopted in generative models. In other words, Tomasello argues that the process of language acquisition involves a huge amount of learning. Recall that cognitive linguists reject the idea that humans have innate cognitive structures that are specialised for language (the Universal Grammar Hypothesis). In light of that fact, we must address the question of what cognitive abilities children bring to this process of language acquisition.

Recent research in cognitive science reveals that children bring a battery of sociocognitive skills to the acquisition process. These cognitive skills are domain-general, which means that they are not specific to language but relate to a range of cognitive domains. According to cognitive linguists, these skills facilitate the ability of humans to acquire language. Tomasello argues that there are two kinds of general cognitive ability that facilitate the acquisition of language: (1) pattern-finding ability; and (2) intention-reading ability.

The pattern-finding ability is a general cognitive skill that enables humans to recognise patterns and perform ‘statistical’ analysis over sequences of perceptual input, including the auditory stream that constitutes spoken language. Tomasello argues that pre-linguistic infants– children under a year old employ this ability in order to abstract across utterances and find repeated pat terns that allow them to construct linguistic units. It is this pattern-finding ability that underlies the abstraction process assumed by Langacker, which we discussed earlier (section 4.2.1).

The evidence for pattern-finding skills is robust and is apparent in pre linguistic children. For instance, Saffran, Aslin and Newport (1996) found that at the age of eight months infants could recognise patterns in auditory stimuli. This experiment relied on the preferential looking technique, which is based on the fact that infants look more at stimuli with which they are familiar. Saffran et al. presented infants with two minutes of synthesised speech consisting of the four nonsense words bidaku, padoti, golabu and tupiro. These non sense words were sequenced in different ways so that infants would hear a stream of repeated words such as: bidakupadotigolabubidakutupiropadoti. . ., and so on. Observe that each of these words consisted of three syllables. Infants were then exposed to new streams of synthesised speech, which were presented at the same time, and which were situated to the left and the right of the infant. While one of the new recordings contained ‘words’ from the original, the second recording contained the same syllables, but in different orders, so that none of the ‘words’ bidaku, padoti, golabu or tupiro featured. The researchers found that the infants consistently preferred to look towards the sound stream that contained some of the same ‘words’ as the original. This shows that pre linguistic infants are able to recognise patterns of syllables forming ‘words’ in an auditory stream and provides evidence for the pattern-finding ability.

Further research (see Tomasello 2003 for a review) demonstrates that infant pattern-finding skills are not limited to language. Researchers have also found that infants demonstrate the same skills when the experiment is repeated with non-linguistic tone sequences and with visual, as opposed to auditory, sequences. Some of the key features associated with the human pattern-finding ability are summarised in Table 4.7.

Finally, this pattern-finding ability appears not to be limited to humans but is also apparent in our primate cousins. For instance, Tamarin monkeys demonstrate the same pattern recognition abilities when exposed to the same kinds of auditory and visual sequencing experiments described above for human infants. Of course, if we share the pattern-finding ability with some of the non-human primates, and if these pattern-finding skills facilitate the acquisition of language, we need to work out why only humans acquire and produce language.

According to Tomasello, the answer lies in the fact that the pattern-finding skills described above are necessary but not sufficient to facilitate language acquisition. In addition, another set of skills are required: intention-reading abilities. While pattern-finding skills allow pre-linguistic infants to begin to identify linguistic units, the use of these units requires intention-reading skills, which transform linguistic stimuli from statistical patterns of sound into fully f ledged linguistic symbols. In other words, this stage involves ‘connecting’ the meaning to the form, which gives rise to the form-meaning pairing that make up our knowledge of language. Only then can these linguistic sounds be used for communication. This process takes place when, at around a year old, infants begin to understand that the people around them are intentional agents: their actions are deliberate and their actions and states can be influenced. The emergence of this understanding allows infants to ‘read’ the intentions of others. Some of the features that emerge from this intention-reading ability are summarised in Table 4.8.

Like pattern recognition skills, these intention-reading skills are domain general. Unlike pattern recognition skills, they are species-specific. In other words, only humans possess a complete set of these abilities. The evidence is equivocal as to whether our nearest primate cousins, for instance chimpanzees, recognise conspecifics (members of the same species) as intentional agents. However, Tomasello (1999) argues that the answer is no. Moreover, these intention-reading skills begin to emerge just before the infant’s first birthday. Tomasello argues that the emergence of holophrases shortly after the infant’s first year is directly correlated with the emergence of these skills.

Tomasello argues that our intention-reading abilities consist of three specific but interrelated phenomena: (1) joint attention frames; (2) the understanding of communicative intentions; and (3) role reversal imitation, which is thought to be the means by which human infants acquire cultural knowledge. According to this view, language acquisition is contextually embedded and is a specific kind of cultural learning.

A joint attention frame is the common ground that facilitates cognition of communicative intention and is established as a consequence of a particular goal-directed activity. When an infant and an adult are both looking at and playing with a toy, for example, the attention frame consists of the infant, the adult and the toy. While other elements that participate in the scene are still perceived (such as the child’s clothes or other objects in the vicinity), it is this triadic relationship between child, adult and toy that is the joint focus of attention.

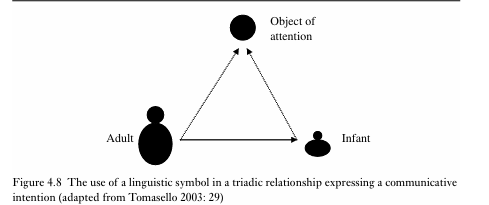

The second important aspect of intention-reading involves the recognition of communicative intention. This happens when the child recognises that others are intentional agents and that language represents a special kind of intention: the intention to communicate. For example, when the adult says teddy bear, the adult is identifying the toy that is the joint focus of attention and is employing this linguistic symbol to express the intention that the child follow the attention of the adult. This is represented in Figure 4.8, where the unbroken arrow represents the communicative intention expressed by the adult. The dotted arrows represent shared attention.

Finally, Tomasello argues that intention-reading skills also give rise to role reversal imitation. Infants who understand that people manifest intentional behaviour may attend to and learn (by imitation) the behavioural means that others employ to signal their intentional state. For example, the child may imitate the use of the word teddy bear by an adult in directing attention to an object. Tomasello (2003) cites two studies that support the view that infants have a good understanding of the intentional actions of others and can imitate their behaviour. In an experiment reported by Meltzoff (1995), two groups of eighteen-month-old infants were shown two different actions. In one, an adult successfully pulled the two pieces of an object apart. In a second, an adult tried but failed to pull the two pieces apart. However, both sets of infants, when invited to perform the action they had witnessed, successfully pulled the two pieces apart. Meltzoff concludes that even the infants who had not witnessed pieces successfully pulled apart had understood the adult’s intention.

In the second experiment, Carpenter, Akhtar and Tomasello (1998) exposed sixteen-month-old infants to intentional and ‘accidental’ actions. The intentional action was marked vocally by the expression there! while the ‘accidental’ action was marked by whoops! The infants were then invited to perform the actions. The children performed the intentional action more frequently than the ‘accidental’ action. Carpenter et al. concluded that this was because the children could distinguish intentional actions from non-intentional ones, and that it is these intentional actions that they attempt to reproduce. In conclusion, Tomasello (2003: 291) claims that language acquisition involves both ‘a uniquely cognitive adaptation for things cultural and symbolic (intention reading) and a primate-wide set of skills of cognition and categorization (pattern finding)’.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة