Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Event-related modifiers

المؤلف:

GRAHAM KATZ

المصدر:

Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse

الجزء والصفحة:

P244-C8

2025-04-27

544

Event-related modifiers

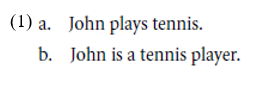

In many contexts the habitual sentence (1a) is synonymous with the generic (1b).

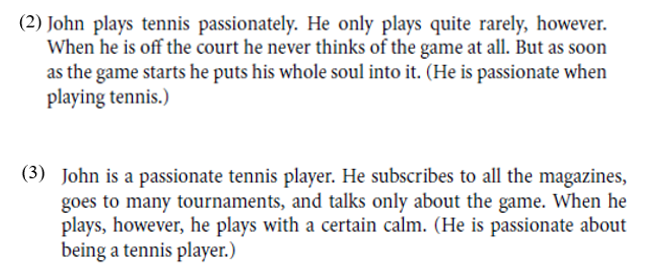

When modified by the adverb passionately, however, a subtle contrast in meaning becomes evident. The habitual has only what we might call the “event-related” reading, made salient in the discourse in (2), while the generic has also what we might call the “state-related” reading, made salient in the discourse in (3).

In the one case, then, the adverb appears to specify something about individual tennis-playing events themselves: each tennis game is carried out in a passionate way. If we adopt a quantificational account of habituals, of the sort proposed by Diesing (1992) and Kratzer (1995) on which habitual sentences involve a sort of quantification over underlying events, then we can think of the adverb as taking narrow scope with respect to this quantificational operator. This is indicated in (80b).1

Essentially this says that every relevant event of tennis-playing by John is a passionate event. We should note that on the Diesing/Kratzer conception, representations such as that in (4b) are not syntactic representation, but rather a post-LF level of interpretation – perhaps the level of Discourse Representation or some other conceptual level.

On the most natural reading of the first sentence of (3), however, it isn’t the tennis games that are carried out passionately, but something else: John is passionate about being a tennis player. Let us consider briefly what this might mean. As suggested above, the passion finds its expression in activities that are associated with being a tennis player, but these aren’t (necessarily) playing tennis. They can be events of traveling to tournaments, subscribing to magazines, etc. In other words the events that distinguish someone who might be characterized as a tennis player from someone who merely plays tennis. It is these events that are carried out with passion.

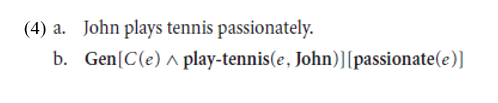

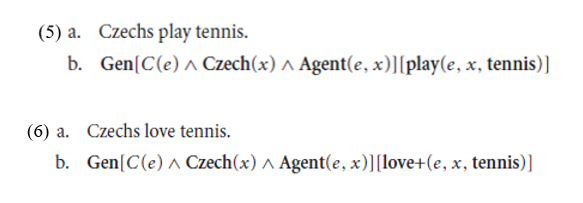

Let us explore one way of turning this observation into an analysis. Chierchia (1995) has argued that generic predicates such as love and know (Carlson’s (1977) Individual-level predicates) should be given a quasiquantificational analysis along the lines of that just sketched for habituals. Both habituals and generic predicates induce a quasi-universal reading of their bare plural subjects – as illustrated in (5) and (6). One of Chierchia’s desiderata is to derive this by providing both kinds of sentences with the same kind of semantic structure.

In both (5) and (6), the free variable introduced by the bare plural subject is bound by the quasi-universal Gen operator, and this is what gives rise to the quasi-universal reading. The difference between these sentences, of course, is what is in the nuclear scope. For habitual predicates it is clear that we are talking about events of playing tennis and so the event predicate play is what is in the nuclear scope. For generic predicates although the claim is that there is quantification over events, there does not appear to be a lexicalized event predicate which is analogous to play. Chierchia’s important innovation was to hypothesize a non-lexicalized underlying event predicate (here love+), which behaves in the semantic representation analogously to play and which appears in the nuclear scope in (6). This hypothesized predicate is intended to be one that holds of events related to the loving of tennis, such as going to watch games, playing tennis, talking about tennis, etc. And the intuition that this proposal attempts to capture is that to claim that someone loves something is to claim something about the kinds of event that they participate in.

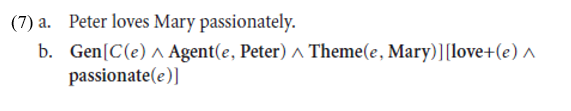

Conceptually there is much to be said for this interpretation. Certainly to determine whether someone loves tennis we observe the range of events that they participate in, and it is from this observation that we draw our conclusion. Likewise, if we are told that Peter loves Mary, we expect there to be a range of events that Peter engages in which reflect this.2 Given such an account of the semantic interpretation of love, it is fairly clear how to treat manner modification. It should be treated along the same lines as manner modification of habitual predicates: that is, the predicate is simply interpreted as occurring in the nuclear scope as a conjoined event predicate. This isillustrated in (7).

What (7b) means, then, is that the relevant events associated with love of which Peter is the Agent and Mary the Theme are passionate. This certainly seems a reasonable interpretation of what it means to love someone passionately.3

This, of course, is all highly speculative. In some ways it is a way of making concrete the claim that the use of manner verbs when combined with state verbs is, in a sense, metaphorical. There is no passionate state, but rather there are passionate events that are closely related to certain states, and we can use adverbials to call up these passionate events, even when talking about states.

1 Gen is taken to have something like universal force (see Krifka et al. 1995), and – like a quantificational adverb – is taken to bind the free variables in its scope. The predicate C is a contextual restriction (of the sort argued for by von Fintel 1994) restricting the quantification to a relevant domain.

2 Common-sense folk-psychology is, in a sense, exactly this approach (Lewis 1972).

3 This analysis bears a number of similarities to the analysis of subsective adjectives (Siegel 1976a) proposed by McNally and Boleda (2004).

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)