Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Productivity measures compared: OED vs. Cobuild

المؤلف:

Ingo Plag

المصدر:

Morphological Productivity

الجزء والصفحة:

P115-C5

2025-01-27

589

Productivity measures compared: OED vs. Cobuild

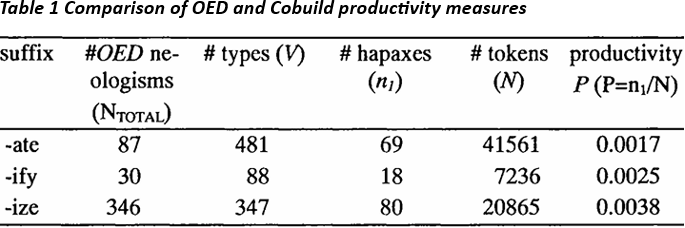

Let us compare the Cobuild and OED figures. For convenience the measures are put together in table 1:

Both the OED measure and the Cobuild Ρ measure show -ize as the by far most productive overt verbalizing affix. Both analyses are also in accordance with regard to the question whether -ate and -ify are productive (they both are), but differ partly in the ranking of the two latter suffixes. How can this discrepancy be reconciled?

Interestingly, the difference only occurs with respect to productivity in the narrow sense. In respect to V and P* the ranking is the same, which is easily understood: the OED is ignorant of token frequencies and only lists new types as they occur, which is basically the same procedure as listing the hapaxes in a text-corpus. Therefore, both data-bases should yield similar results (if the corpus is representative and the OED coverage is good).

In the OED data, the ratio of -ify neologisms to -ate neologisms is somewhat higher than the ratio of the respective Cobuild hapaxes (0.34 vs. 0.26), which is explained by the fact that the number of -ate hapaxes in eludes fewer neologisms. The almost identical ranking of -ify and -ate in the dictionary-based count on the one hand, and in terms of V and P* on the other is therefore strong evidence for the accuracy and versatility of the OED data.

One difference between the two data sets should not go unnoticed. In the OED, -ize neologisms are much more frequent than -ate neologisms, whereas in terms of Cobuild hapaxes the difference is small. As already mentioned above, the number of -ate hapaxes does not reflect the proportion of neologisms as accurately as assumed. The proportion of neologisms is high among the -ize hapaxes, but low among the -ate hapaxes. The calculation of Ρ corrects the wrong impression of -ate as gained on the basis of P* alone. The text-based analysis brings out this double-faced character of -ate (high global productivity, low productivity in the narrow sense) quite clearly, whereas the OED figures cannot bear witness to it.

But why is -ate significantly more productive than -ify according to the OED measure? It seems that two factors may be responsible for the good result of -ate in the OED. For one, it could be an artefact of the sampling method. By not excluding a priori certain kinds of -ate formations I ended up with more derivatives than actually belong into this category. As will be shown in detail, only 25 of the 72 derivatives ( i.e. Ν in table 1) are actual exponents of the productive rule of -ate formation, which would set -ate on a par with -ify.

The second factor influencing the high number of -ate neologisms in the OED can be found in the nature of the data base itself. A look at the productive -ate formations in the OED reveals that the majority of them are highly technical terms cited mostly from scientific texts. The Cobuild corpus, however, represents a very broad range of text types (see Renouf 1987), so that the chance of encountering new terms from a highly specialized domain is relatively small. On the other hand, in a comprehensive dictionary like the OED marginal text-types with a high rate of innovational terms, such as scientific writing, must necessarily be overrepresented with their neologisms. This explanation is in line with earlier observations in corpus-based studies that there are significant differences in word-formation patterns across different text-types and styles (Baayen 1994, Baayen and Renouf 1996).

To close our discussion of table 1., let us consider why -ify fares much better than -ate in terms of Ρ in the Cobuild corpus, which seems to contradict the OED measure. This contradiction is, however, only apparent, since Ρ is of course also dependent on text types, so that parallel arguments hold for Ρ as for P*. Furthermore, the OED measure cannot reflect accurately the probability measure P, because token frequencies do not play a role in its calculation. Thus the OED measure reflects at best the probability of encountering a new derivative in a given period, whereas Ρ reflects the probability of encountering a new derivative among other derivatives of the same type. Strictly speaking, these are two related, though inherently different things, as became clear in our above discussion of adverbial -ly in the Times corpus.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)